Date on your own terms! Join the other couples who have dated and married through myTamilDate.com!

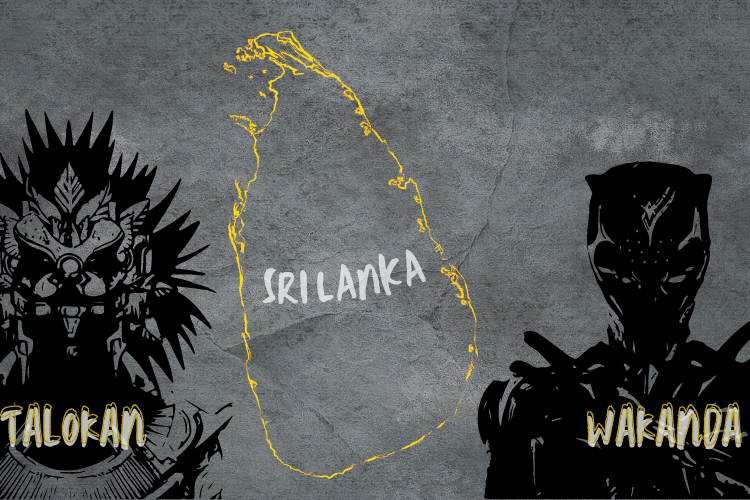

If you watched the recently released Black Panther - Wakanda Forever, you might have noticed something interesting (or not - maybe I just need to be less analytical): Wakanda and Talokan are supposedly the only two vibranium-rich countries in the world, making them natural allies; but they go to war with one another instead, even though the root of their anger comes from the global powers that are the cause of their misfortunes and need for secrecy. Science fiction aside, this element of the movie offers a glimpse into how intentional colonial strategies turned largely peaceful communities against one another in Sri Lanka, and dozens of colonised countries around the world.

“Divide and rule” is a strategy that was used effectively by colonial powers to turn communities and ethnicities against one another. You can see the logic behind it: splitting ethnic groups into hierarchies, and giving one group more rights, power and opportunity creates internal divisions. In Sri Lanka, there is plenty of evidence (see sources below) to show that the British administration provided Tamils with better education and employment opportunities, while the Sinhala population was marginalised. Tamil was spoken in other parts of the British Empire, giving the British incentive to educate Tamils as civil servants to facilitate economic opportunities for the empire. As Tamils gained increasing clout as an English-educated upper class, their power and influence in comparison to the Sinhala population continued to grow, creating clear class distinctions and further inequality between the two ethnic groups, caused directly by British policies.

This was a deliberate strategy the British used elsewhere, and it makes sense: if united, colonised populations could combine their manpower and resources to take on the outside threat, or grow their political influence to question the authority of colonial governments. But divided (or better yet, fighting each other) their strength and anger would not be directed at their colonial overlord.

This is a strategy that was used effectively to incentivise and divide Hindus and Muslims in India, Aboriginal communities in Canada, and communities throughout its empire in Africa, among others. To say that British colonialism created all of these divisions is not accurate; there were, and always have been, internal divisions between religions and ethnicities in Sri Lanka. But it was colonial policies that brought these divisions to the scale of fighting seen before and during the civil war.

Listen to our new podcast 'Identity'!

Shakthi / Theatre, Intergenerational Trauma and Australian Tamil Identity

In the fictional universe of Black Panther, Wakanda is a prosperous but secretive country. Though never colonised, it is subject to the greed of the world’s powers, forced to hide its success and advanced society as a means of survival. In the first Black Panther movie, this is taken a step further by showing Wakanda through the eyes of Michael B. Jordan’s character: Killmonger sees Wakanda as being capable of lifting millions of communities in Africa out of poverty, but the Wakandans see this as impossible, knowing that exposing their technology to the world will bring about their own subjugation by a long line of countries hungry for vibranium. As a result, while they are a technologically advanced society, they are under constant threat and danger from more powerful nations; any overt misstep would threaten their survival. But at the same time, Wakanda has also benefited from its position on the world stage.

Since the world knows Wakanda can offer a lot of value in trade, technology and vibranium, it is a well-connected powerhouse and regional superpower, and has eager partners should it choose to accept them. Talokan, on the other hand, though very similar to Wakanda, has not seen any such benefits. The flashbacks seen in the film show that the roots of Talokan’s oppression lie in colonial violence; since his forced exile at the hands of Spanish colonisers, Talokan’s leader Namor and his people have been hidden away, no doubt seeing Wakanda prosper in the very system that caused Talokan’s exile. With little to lose, Namor is more than willing to wage war on the world to increase Talokan’s international standing and level the playing field. As the only apparent vibranium-rich societies in the world, Namor offers an alliance between Wakanda and Talokan, with the caveat that refusal would mean war. But Wakanda, with a comparatively better position within the world order and an isolationist foreign policy, does not want to destroy it. The end result is a war between two victims of the same system, a struggle for power and recognition that harms the other.

If you see parallels to Sri Lanka, there are many. Colonial policies intentionally sought to increase divisions between Tamils and Sinhalese; with Sinhala anger safely directed at the more privileged Tamil community, the British administration ensured its own safety from the anger and resentment it was so deserving of for creating that system in the first place. As history has shown, the Sinhala and Tamil communities did not combine their forces to get the British out of Sri Lanka. Instead, the British left largely on their own with their system in place, ensuring that the power struggle they had created between Tamils and Sinhalese would play out in the next decades.

Upon independence, the new Sri Lankan government instituted widespread policies, including the Sinhala Only Act, that favoured Sinhala representation in employment and education. Efforts to oppress and intentionally limit Tamils’ rights and representation contributed to further tension, division, militancy, pogroms and eventual war.

Yes, Black Panther is a movie in a fictional universe, and there is much more to the movie and to colonialism than what I have outlined. But the message is the same. The opening few minutes of the movie show a scene at the United Nations, with the camera lingering tellingly on the French and American representatives, indicating who the antagonists in the story are. By the end of the movie, however, Namor is shown hinting that the war has not ended, thereby replacing the global powers mentioned at the beginning as the story’s main antagonist and villain. This is colonialism and the divide and rule policy summed up perfectly. The oppressed can turn on one another, to the benefit of their colonial overlord. In the end, the coloniser’s hands are clean, and they are free to watch their former victims tear each other apart. This is what happened in Sri Lanka, and dozens of other colonised countries around the world.

Sources

- https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2017/8/10/the-partition-the-british-game-of-divide-and-rule

- https://hir.harvard.edu/sri-lankan-civil-war/

- Soherwordi, S.H.S (2010). Construction of Tamil and Sinhalese Identities in Contemporary Sri Lanka. Pakistan Horizon, 63(3), 29-49.

- Lin, David, "The Role of British Colonial Policy in the South Sudanese Civil War: A Postcolonial Conflict Analysis (2018)" (2018). International Studies Undergraduate Honors Theses. 26. https://scholarworks.seattleu.edu/intl-std-theses/26

- What Policies Cannot Express: An Examination of Sri Lanka’s Continuing Inability to Bridge the Sinhala-Tamil Ethnolinguistic Divide through National Policies and Programs. Bowdoin College. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/214030152.pdf

READ NEXT

Tamil Innovators: V.T. Nayani On The Power Of Storytelling

Tamil Innovators: Noel Kirthiraj, CEO Of Maajja, On The Future Of South Asian Music