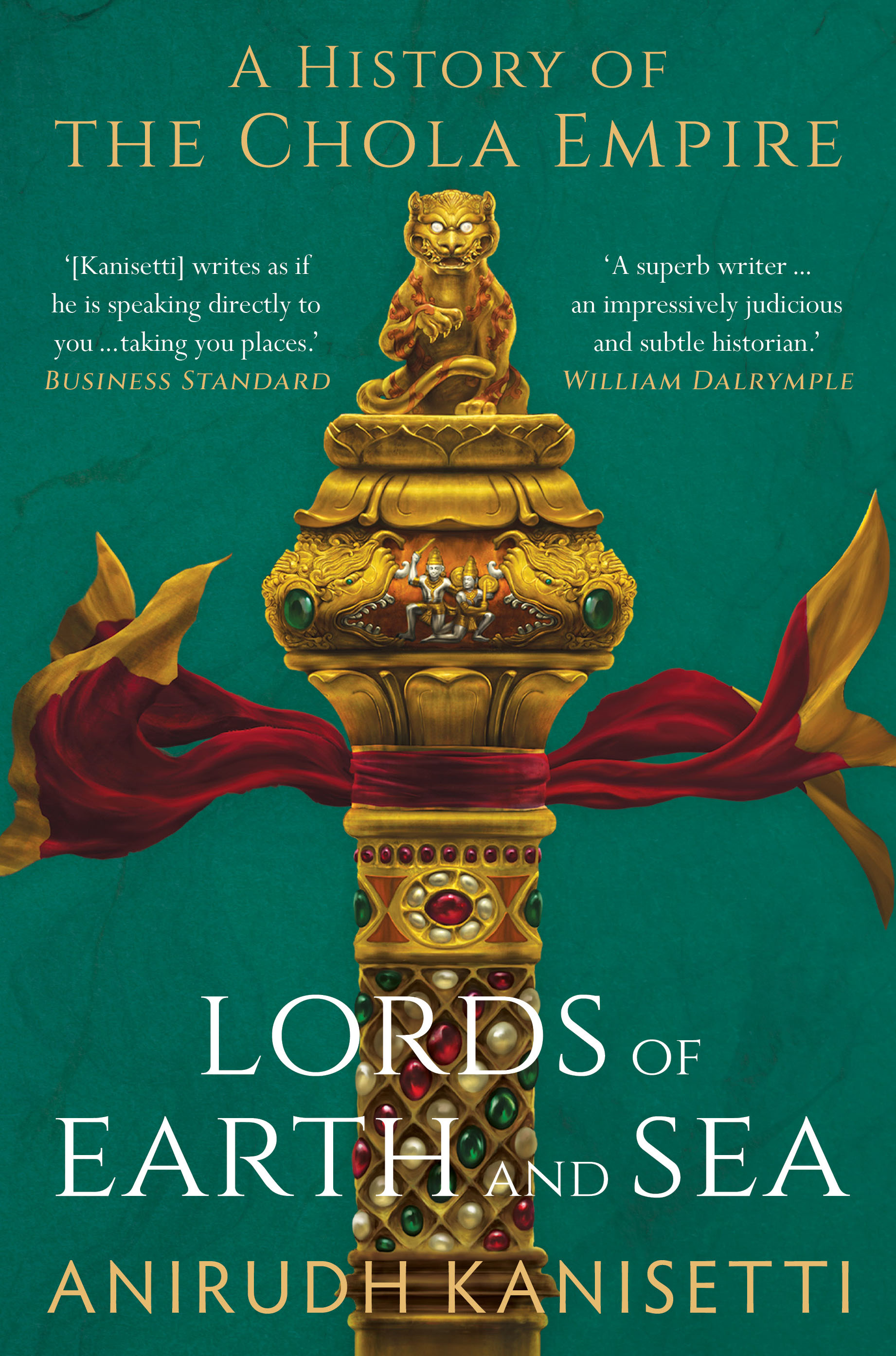

Anirudh Kanisetti, an award-winning historian and author of Lords of the Deccan, recently spoke to TamilCulture about his highly anticipated upcoming book, Lords of Earth and Sea. In the conversation, he explored the role of history in shaping our modern world and shared discoveries about the Chola kingdom that deepened his appreciation for their society and innovations. By examining the lives of both rulers and commoners, he emphasizes how history can inspire us to understand resilience, inclusivity, and sustainability in contemporary times. Book available to purchase here: Amazon

An excerpt from the book, on building of the Brihadishwara Temple, is available here: Link

Do you think young South Asians are showing a renewed interest in their historical identities, particularly as anti-colonial perspectives have gained popularity in recent years?

I would argue that the process of rediscovering Indian culture is not a new one but rather a deeply rooted and ongoing journey. For instance, if we look at the early 20th century, we see the writings of great historians like Nilakanta Sastri, who authored one of the first comprehensive histories of the Cholas. That interest in India’s historical identity was already apparent at the time.

However, the way this interest is evolving today is distinct. It is heavily influenced by the widespread penetration of the internet, which has made historical knowledge and cultural narratives more accessible than ever. Additionally, the gradual improvement in income levels has afforded people the time and curiosity to engage more deeply with these pursuits. Politics also plays a significant role. It’s undeniable that India has experienced a majoritarian trend in recent years, and this shift often incorporates efforts to forge a shared identity that unites the nation.

While decolonization is undoubtedly part of the equation, it’s worth noting that many of those championing cultural rediscovery belong to the very classes that benefited from colonization—such as anglophone elites and upper castes. This makes the process complex and multilayered. It’s not just about breaking free from colonial legacies, nor is it an entirely organic development. Instead, it’s both organic and influenced by larger conglomerates, political coalitions, and aspirational groups.

The Cholas are widely celebrated for their remarkable achievements and enduring influence, which continue to resonate deeply with Tamils worldwide. In your opinion, what distinguishes them from other Indian dynasties?

By medieval standards, the Cholas were an incredibly creative and visionary dynasty. They consistently demonstrated a willingness to challenge and transcend older traditions and norms, building entirely new and unprecedented systems. Perhaps the clearest example of this is the Chola Empire itself.

Throughout South Asian history, it was rare for a coastal polity to rise as one of the dominant powers of the subcontinent. The Cholas achieved something unprecedented—they established a sustained hegemony that spanned nearly three centuries, extending from the Tamil coast into the highlands and beyond. Their military reach was equally remarkable: they deployed armies as far as Bengal and even sent detachments to Southeast Asia. Such long-range campaigns and influence were unmatched by any South Asian polity before them.

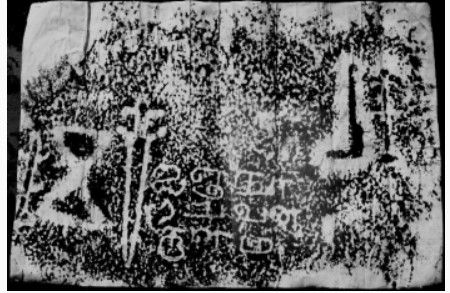

Tank inscription of Ainnurruvar, 13th Century CE, Pozhichalur, Kanchipuram District

Source: Government of Tamil Nadu - Department of Archaeology

A key factor behind this success was the Cholas’ ability to forge innovative alliances. One of the main arguments in my book is that their alliance with the Ainnurruvar, or the 500 Merchant Guild, was instrumental. This network of merchants and landlords, which predated and outlived the Cholas, played a pivotal role in their rise. The Cholas harnessed the guild’s trading networks and merchant shipping to expand their logistical capabilities, enabling their armies to explore and conquer new frontiers.

This creativity wasn’t limited to their political or military strategies—it extended to their architectural and cultural endeavors as well. The Rajarajeswaram temple wasn’t just a place of worship, it was a statement of imperial ambition. It brought priests from across the Kaveri floodplain, integrating them into a shared ritual framework that symbolized the Chola vision of a unified state. Rajaraja Chola’s intent was clear: to create an empire that transcended local identities and incorporated diverse peoples into a grand imperial framework. This was further reflected in their administrative structure, which included officers and generals not just from Thanjavur, but from across the region, including Tondai Nadu (the old Pallava heartland) and even former Pandya territories.

The Cholas possessed an extraordinary transregional imagination. They were not confined to their homeland but instead envisioned and executed the creation of a true empire. Their ability to think beyond conventional boundaries, to build, administer, and innovate, places them among the most remarkable figures not only in medieval India but in the medieval world at large.

Your book, Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire, is the result of extensive research. Could you share what that process was like? What was the most unexpected place where you uncovered a piece of history?

The Cholas—and, more broadly, medieval Tamil people—were exceptional chroniclers, their records meticulously carved into temple walls. This commitment ensured their records would endure through time, allowing us to reconstruct Tamil society with unprecedented detail. While other Indian cultures also kept records, the preservation methods differed, such as the use of palm leaves, which did not survive the ravages of time.

These records provide us with a clear view of how temples functioned and their role within society. Though this perspective is somewhat temple-oriented, scholars can make informed inferences about broader societal relationships. For example, we can track where a general was stationed year by year or analyze how kings framed their conquests differently depending on the audience they addressed. This allows a view into medieval society that, while different from ours, mirrors modern society in its complexity and dynamic interconnectedness.

For me, one of the most remarkable discoveries was the existence of a Tamil temple in Guangzhou, China, established in the 13th century under the Yuan Khanate—the descendants of Genghis Khan who ruled China. The Yuan dynasty had a keen interest in global trade, and, somehow, a Tamil-speaking diaspora had taken root in this major port city. They built a temple there, and its foundation inscription has survived.

The inscription reveals that the temple was established by a firman (a royal decree) from the Mongol Khan. The most striking detail is the temple’s name. Chola kings typically named temples after themselves—for instance, Rajaraja Chola named his temple the Rajarajeswaram. Yet the temple in Quanzhou was called the Khaneeswaram, or "Temple of the Khan." Some scholars argue it could also be Kadal-eeswaram, meaning "Temple of the Ocean" but either interpretation is intriguing.

To me, it’s astonishing that a thread of Tamil culture found its way to such a distant and unfamiliar shore, taking root in a form that remains recognizable as Tamil, even in its globalized expression. It serves as an incredible example of how Tamil culture, centuries before the modern diaspora, spread across the world and left its mark—something that resonates deeply with the Tamil diaspora today, of which you yourself are a part.

The Song Dynasty’s Empress Liu, Zhenzong’s consort and regent, wearing a headdress of pearls.

Might some of these pearls have come from Rajaraja Chola’s embassy? Source: National Palace Museum/Wikimedia Commons

Did your views on the Cholas evolve as you conducted research for this book? Were there any discoveries that shifted your perspective?

Absolutely, my perspective on the Cholas changed significantly during the course of my research. When I wrote my first book, Lords of the Deccan, the Cholas were largely antagonists to the Deccan kings. It’s similar to how Napoleon is remembered differently depending on where you stand: in France, he’s a national hero; in Russia, he’s a foreign invader and despoiler.

Arulmozhii Chola and three of his queens, depicted later in life.

Source: Archaeology Survey of India

There’s no denying that Chola conquests often had devastating consequences for non-combatants. I address these in detail in the book. At the same time, examining the personal circumstances that shaped figures like Rajaraja Chola provided a more nuanced understanding. Rajaraja grew up in a tumultuous environment: his brother was assassinated, his father essentially withered away, and his mother committed suicide. He was raised in the court of his uncle, Uttama Chola, an administrator who avoided warfare. These experiences likely influenced Rajaraja to mold himself as an adventurer and conqueror. Unfortunately, in the medieval world, conquest often involved violence to assert claims of power and legitimacy.

For me, the most profound discovery was understanding the Cholas as both creative and imaginative rulers as found in their inscriptions, which were often written in Tamil and aimed at Tamil audiences. Tamil society at the time wasn’t structured in a centralized way; it was highly village-oriented. Village assemblies made crucial decisions about cultivation, irrigation, harvests, law enforcement, and fines. In this relatively self-contained and self-governing environment, the question arises: what was the role of a king?

The Cholas were constantly answering this question through their actions. By building grand temples and endowing them with wealth. Their inscriptions often implied a message to the people: “We are great conquerors, we support your gods, we keep your taxes low—follow us.” They frequently revisited the same sites and carefully chose which temples to endow to ensure their message reached a diverse audience. Often, local chiefs followed their example, making their own gifts to temples where Chola kings had donated, showing that the royal message had been accepted and internalized.

To me, this was extraordinary. It revealed the Cholas not only as rulers and politicians but also as deeply human. What is more human than the desire to communicate and be heard?

Check out Season 2 of our Identity Podcast!

Topics like the Cholas often inspire strong opinions. How do you handle disagreements or opposing views about your work?

Debate is essential. Not only is it an integral part of Indian culture, but Tamil culture, in particular, has a rich tradition of debate and disputation. I’m happy to contribute to that tradition because meaningful conversations about history are crucial.

We would all agree that modern people are complex, existing within shades of gray. To insist that the people of the past lived in binary terms—entirely good or entirely bad—is to deny them their humanity. That denial is, in its own way, a profound act of violence against history.

To do justice to the medieval Cholas, or any historical figures, we must embrace their complexity. We must allow them to exist as interesting, multifaceted people who lived in morally complex times. By discussing everything they did—their achievements, their failures, and the violence they committed—we grant them the dignity of being fully human. Only then can we truly honor and learn from history.

You’ve been critical of the Ponniyin Selvan films. While it’s a work of historical fiction, what do you think the films could have done better to capture the essence of the Cholas and their era?

To some extent, the film was constrained by its source material, which itself stems from a very specific cultural and historical context. There’s an intriguing interview with Gowri Ramnarayan, the granddaughter and translator of Kalki Krishnamurthy’s work, where she mentions that Kalki modeled Arun Mozhi’s character on the qualities he admired in great nationalist leaders of the time. Kalki saw Arun Mozhi as embodying the steel of Sardar Patel, the erudition of Jawaharlal Nehru, and the humility of Mahatma Gandhi. Ponniyin Selvan is a product of the 1950s, reflecting that era's aspirations and the emergence of a Tamil nationalist consciousness. Within the constraints of adapting such a beloved book, I’m not entirely sure what could have been done differently while staying true to Kalki’s vision.

However, one area where the films fell short is in the historical accuracy of their art direction. For instance, the depiction of 16th-century Portuguese ships is anachronistic and doesn’t reflect how medieval Indian ships actually looked. Medieval Indian temples and palaces were vibrant, bursting with color and textiles. The Ponniyin Selvan films, with their relatively muted color palette, don’t fully capture the vibrancy of medieval India.

A model of a small Indian Ocean vessel, based on the Borobudur reliefs, c. ninth century

Source: Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, UK

More than being critical of the Ponniyin Selvan films specifically, I am critical of how Indian filmmakers often choose to represent medieval India. Many of these portrayals lack consultation with historians. For me, that’s the core issue. Instead of relying on larger-than-life narratives that ultimately feel unsatisfying, filmmakers should engage with historians. The real stories of medieval India are far more fascinating, layered, and dramatic than anything fictionalized for the screen. By collaborating with experts, filmmakers could craft more authentic and compelling portrayals of India’s rich past.

Popular history often carries biases due to external influences or personal perspectives. How do you ensure your work stays balanced and objective?

It’s hard to recognize when you’re being biased because some beliefs are so deeply ingrained that you might not notice how they unconsciously influence your work. To counter this, I share my work with fellow historians and ask for their most honest, even brutal, feedback. But ultimately, I believe none of us can have the final say about people who lived a thousand years ago. There will always be new interpretations, discoveries, and ideas that enrich and complicate our understanding of the past.

As a public historian, I feel a responsibility to show people how historical ideas are developed. When you read my book, you’ll notice that I meticulously footnote and cite every argument I make. I believe it’s essential to remain transparent about the process of historical inquiry. One important aspect we often forget is that, for most of history—up until the linguistic states were formed just a few decades ago—our societies were multilingual and followed diverse customs. South India, in particular, stood out as a cosmopolitan hub with a vibrant exchange of ideas, languages, and poetic forms. The adikavi (first poet) in the courtly Telugu tradition was Nannayya, a Tamil Brahmin; the adikavi of courtly Kannada was Pampa, a Jain from Andhra. Some of the greatest works of Carnatic music were written by Tyagaraja in Tamil Nadu using the Telugu language. In my book, I aim to honor this shared South Indian heritage by discussing the Cholas in a transregional context.

The bronze imperial seal of Rajendra Chola I, depicting the Chola family’s tiger framed by the Pandyas and Cheras symbols.

Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Wikimedia Commons

The Cholas belong to all Indians. Drawing rigid lines and claiming certain aspects of history exclusively for specific groups is counterproductive. Being Telugu doesn’t make me any less qualified to write about the Cholas, especially since I rely heavily on the scholarship of Tamil historians, whose work I deeply respect.

This project is my offering to the ongoing rediscovery of Tamil literature, culture, and history—a culture I’ve come to admire profoundly since beginning this journey. I hope readers approach the book in that spirit of shared respect and curiosity.

Why is it important to understand history? How much of a role do you think historical details influence power and privilege in the present and future?

The single most important reason to understand history is that it reveals how power operates. It shows how power develops, sustains itself, and communicates its narrative. For the citizens of a democratic country—and a democratic world—there is nothing more vital than understanding the mechanics of power.

More broadly, history teaches us that society, politics, and even religion are not fixed, eternal entities. They evolve. Gods evolve. Temples evolve. These transformations occur in response to forces of power and societal currents.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of writing my book was tracing how places like Chidambaram transformed over centuries. Generals, ministers, and aristocrats continually patronized the temple, introducing new rituals, shrines, and even recipes for temple prasadam. Today, when you visit a temple, you might be told it was established 5,000 years ago, but such claims obscure the centuries of creativity, evolution, and human effort that shaped it.

For example, seeing Sembiyan Mahadevi’s first Nataraja sculpture at Konerirajapuram—a small, polished, dark stone image—was deeply moving. Centuries later, that same god stands in Chidambaram, a magnificent bronze figure still worshiped by Tamils. The sheer continuity and transformation overwhelm you with a sense of how much history has unfolded in our land and how countless lives have contributed to it.

There’s often a tendency to think of history as the story of kings, but ironically, studying the Cholas—arguably Tamil Nadu’s most famous rulers—has reinforced for me the agency of ordinary people. Time and again, merchants, village assemblies, and caste groups emerged as key players, negotiating with kings and shaping history in ways that are often overlooked. This has broadened my understanding of history—not as a procession of kings but as a tapestry woven by millions of ordinary people, as complex, messy, and creative as any of us.

This is why we should study history. It reminds us of what it means to be human and the profound responsibility we carry as participants in shaping the world for future generations.

Lords of Earth And Sea : A History of The Chola Empire available to purchase here: Amazon

Check out Season 1 of our Identity Podcast!