My films are always imperfect, raw, genre jumping, straight from the voices of the community that spoke truth to power.- Leena

Catch screenings of Leena’s Maadathy and Kaali on March 15, 2023 7pm at Innis Town Hall, Toronto. For more info visit: uoft.me/8QG

Gender and social justice are key themes that you explore in your films. How did your childhood and life experiences shape your views on these themes?

Gender is nothing but indentured labour in brahmanical patriarchy. My mothers and grandmothers were exploited as both labouring and reproducing bodies to maintain land, ethnic purity and caste pride. I wanted to break that chain of slavery. I protested every given gender role and expectations. My thirst for justice is my thirst for being a person of my choice and owning up my story. My childhood was my violent rupture from subordination and thrusted identities. Nothing scares the system than a female existence with agency, voice, opinions and sexuality. Every single force would want to crush my existence. My resistance to be crushed defined my life experiences and evolved my politics.

Leena on location for Parai (2004), the first ever Tamil documentary where Dalit women speak about sexual harassment on camera. Excerpt from Parai available here

Many of your work features rural cultural practices. What is your fascination with them and are you using your medium as a means to document these traditions?

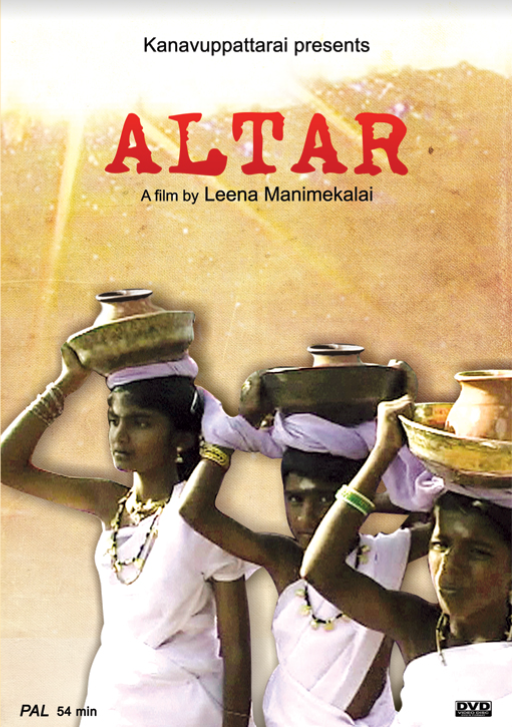

Leena on the location in Karur, Tamil Nadu for her documentary பலிபீடம்/Altar (2005)

I am a daughter of western ghats. My native village under the slopes of Sathuragiri mountains is where Tamil anarchist poets Siddhars were believed to have lived over 1000 years. Srivilliputhur the town where I was brought up has a temple for Poet Andal and it stands tall in Tamilnadu emblem. I come from an agrarian family and I grew up worshipping small gods and deities. I am all at once காட்டு நெல்லி (kaatu nelli), மானம்பாரி (maanampaari), எள்ளுச்செடி (elluchchedi), புளியம்பழம் (puliyambalam), மாவூத்து (maavooththu), வரையாடு (varaiyaadu), குற்றாலச்சாரல் (kuttralachcharal). I am nothing if you remove the Mariyamma’s spirit from me. I am walking in my ancestors' feet and they include all the wild trees of செண்பகத் தோப்பு (senbagath thoppu)

Cover of பலிபீடம்/Altar (2005) a documentary intervention exploring the child marriage practices that exists within the Kambalthu Naicker community in central Tamil Nadu. Excerpt from Altar available here

Date on your own terms! Join the other couples who have dated and married through myTamilDate.com. Join Here.

Not coming from a filmmaking background, what was the biggest revelation that you had when you started off in the Tamil film industry?

I am a first generation filmmaker. My father did not have a wikipedia page. I am coming from a place where female representation is less than one percent as authors in cinema. I had to throw myself into the abyss, trial and error, be banished and burnt, to find my way out. I found my voice when I realised I have to create my own image and not a perceived one. One thing I know for sure is that, nobody would have gotten to know the stories, if I had not filmed them. My filmography and bibliography is my ஒற்றையடிப் பாதை (ottraiyadip paathai). I had to cross, burn, and destroy hundreds of fences to find it.

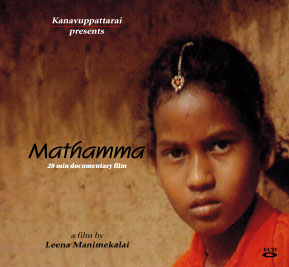

Mathamma (2003) captured a peculiar practice of devoting girl children to the deity of the folks of Arundhatiyar community, Mangattucheri village near Arakkonam, Chennai. Excerpt from Mathamma available here

Contrary to many others who begin their filmmaking journey with either short features, feature films or even advertising, your first work, Mathamma, was a documentary, As was many of the work that followed. What was it about this style of filmmaking that appealed to you?

I grew up watching films that profited by insulting and humiliating women. Growing up,I could never identify with the women shown on silver screens. It was all feudal masochist in nature. The industry practices are also hierarchical, misogynist and casteist. I was a misfit in the film industry. I picked up filmmaking from the streets. Revolution in digital technology democratised the resources and I got access to cheap cameras and software. I was hardly twenty when I made my first documentary. I went in my scooty wound with microphones to film my people. All I learnt is from them. My films are always imperfect, raw, genre jumping, straight from the voices of the community that speak truth to power. None of my films were ‘projects’. They were my ‘calling’ and one led to another. My life as a filmmaker is the story of my total submission to the truths I found, love and solidarity to my people and their struggles and fierce resistance to censorship. Everything else is a bonus.

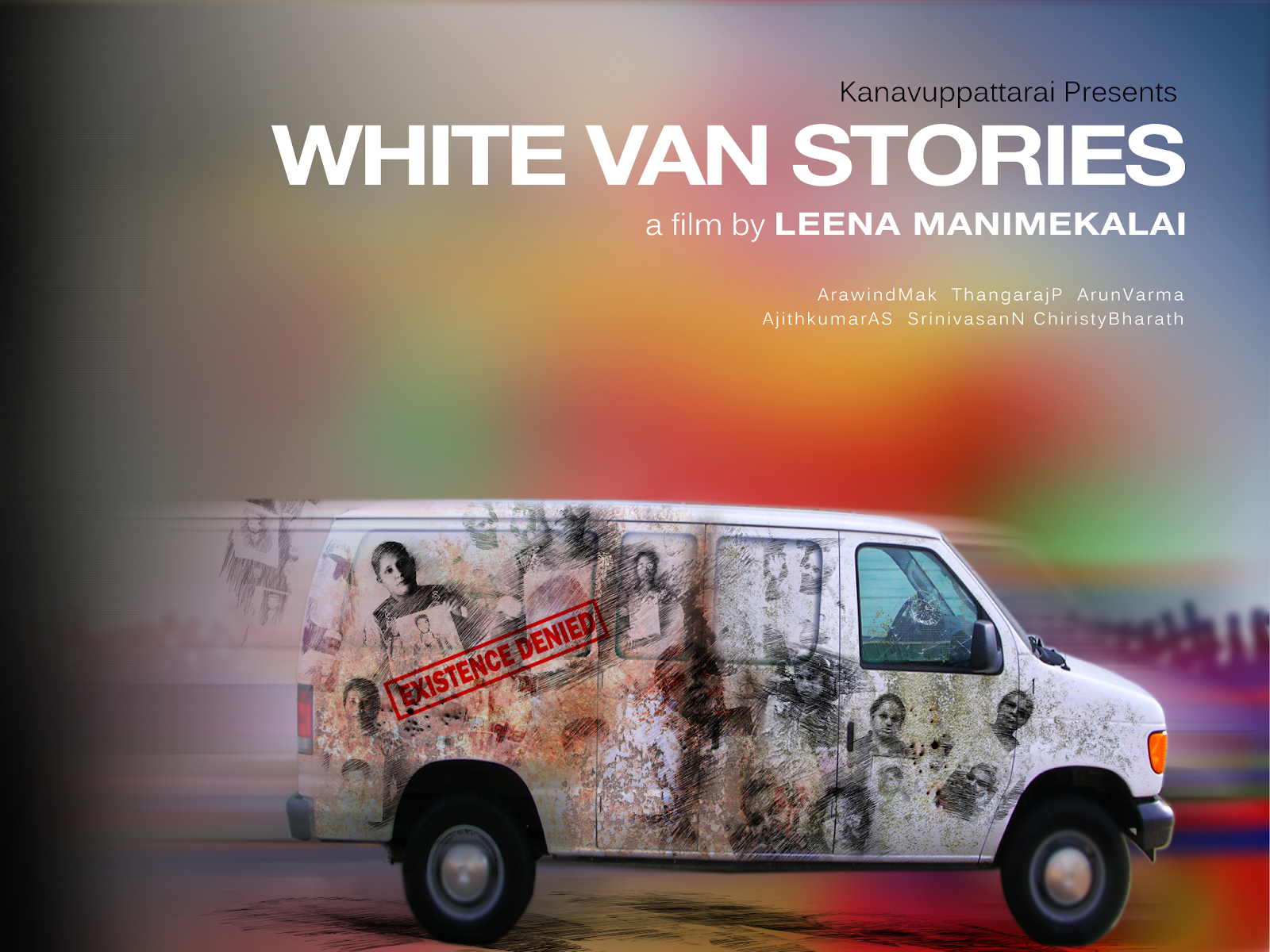

Documentary cover of White Van Stories (2013) captures the plight of families of missing persons in Sri Lanka. Promo available here

Probably the most risky documentary that you have made is “White Van Stories”. It’s been 10 years since, but the topic of missing persons in Sri Lanka remains a matter of concern and families are still awaiting answers. Can you tell us how this project came to be and the experience of filming it? Have Jaya, Rasiya & Sandya, and the family members featured in the film, found any answers?

They will never find answers. They protest to keep their questions alive. They are the only voices still lingering out of the whole war fought for Tamils’ right to self determination. When I attended the first ever Ilakkiya Santhippu held in Jaffna, post war, I stayed back and volunteered in the steering committee of activists. We were mobilising the families of the disappeared from North, East, South and the Hills for a potential protest in Jaffna around the then, UNHRC Commissioner, Navi Pillai’s visit. I travelled throughout Sri Lanka meeting the leaders, families and the allies. That journey was life altering, preparing me to risk everything to document their stories.

I was stopped, interrogated, my tapes confiscated and at one point sent back to India by the Sri Lankan Military Forces. I had my own ways to return to filming. Thanks to the warrior women and their resilience like Vetrichelvi and others, that the film was made. They fed me, protected me and trusted me with their stories. My risks were nothing before the mountains they move everyday.

Catch episodes of our latest podcast 'Identity'!

- Shakthi / Theatre, Intergenerational Trauma and Australian Tamil Identity

- Identity Podcast: Anuk/ Language, Grief and Tamil Community

- Maral/ Art, Belonging & Armenian-Iraqi-Canadian Identity

- Identity Podcast: Shuba/ Music, Feminism and Dual Identities

How the film got a broadcast opportunity was serendipity. I had cut a trailer and tweeted - tagging the Channel Four team. In a few hours, I got an invitation to fly to London, edit the material into different lengths and broadcast them. It was a high voltage experience broadcasting the film while the British PM Cameron was attending the CHOGM sessions in Colombo. It was surreal to witness the characters in the film blocked from meeting Cameron right after the broadcast and him taking the train to Jaffna and finally being able to meet and hear them. It was one week of broadcast activism. I was under high security protection until my return to India. All that the Tamil community offered was additional constitutional ban, malicious hate propaganda, slander and hate.

Leena’s first feature film Maadathy (2019). Maadathy trailer available here

How did the transition from being a documentary filmmaker to a feature filmmaker come to be? And why did it take till Madathy to get there?

First ever film in the history of cinema is factual cinema. I respect both factual and fictional cinema. Subjects I choose, decide the genre of storytelling. Tamil society considers only hyper masculine, hyper real masalas as cinema. I belong to the transnational legacy of cinema. Kurosawa, Kiarostami, Agnes Varda, Chantel Akerman, Maya Deren, Ritwik Ghatak, G Aravindan are my ancestors. Rare Tamil films like Aval Appadithan, Pasi, Veedu did earn my respect but I am largely uninspired by Tamil Cinema.

Leena on location for Sengadal (2011) in Danushkodi, Tamil Nadu, filmed in the Cinema Verite structure. It was yet another daring work that follows the lives of Tamil fishermen and the atrocities that they face at the hands of the Sri Lankan Navy. Trailer available here

You may guard this closely but can you give us a glimpse of what your process is like from the time you have an inspiration all the way to having that final script/screenplay ready to be filmed?

Total surrender is my process. I keep myself widely open throughout the process of seeking, finding, discovering and creating. When I could handle my ‘knowing’ and not define my ‘feeling’, I create good art. Writing is where I build my worlds. Rest is all execution. I fail 99 times and what surfaces is just that 1 percent.

‘Kaathadi’ was your thesis project during your Master’s in Fine Arts in Film degree program at York University. It was quite an ordeal for you to get there; fighting defamation, getting your passport impounded and your perpetrator even writing to the University to pull back your visa. How supportive was York U throughout this and how did these elements shape Kaathadi?

Kaathadi is my personal memoir. It is my catharsis of being born as a shudra Tamil queer female body. I was trying to address generational trauma of a gendered existence with a hybrid film woven with poetry, dance, movement theatre, architecture/landscape, music, drama and documentary. My department at the York University, Professors and Cohort had my back and in fact rooting for me through my struggles with covid waves/lockdowns, #metoo defamation cases, passport impoundment and my legal fights. Even during the post ‘Kaali’ situation that was done as a project for TMU’s CERC Migration, my Professors at York University took initiatives and ran a signature campaign collectively with the community of artists/academicians/scholars in Canada, in solidarity with my art and fight.

But the reaction to Kaali shook my supportive ecosystem in York University too. My Supervisor stepped down a few weeks before my defence stating that his safety will be at stake. That really broke me down more than the life/rape threats and state persecution. I was assigned a new Supervisor and he took my film for legal opinion, without my consent, stating the film is too ‘sensitive’. I wrote to my dean and withdrew from my MFA program as I felt violated of my rights. Then the equity committee and well meaning feminist-queer activist Professors intervened and came on board as my supervisory committee.

Kaathadi flew with full freedom. Life wasn’t satisfied with this much and I was shattered once again with the sudden demise of my dear collaborator-composer-sound designer Phil Strong just one week before my oral defence. Kaathadi the film, the support paper of 80 pages and the oral defence was all about picking my pieces. So many births and deaths.

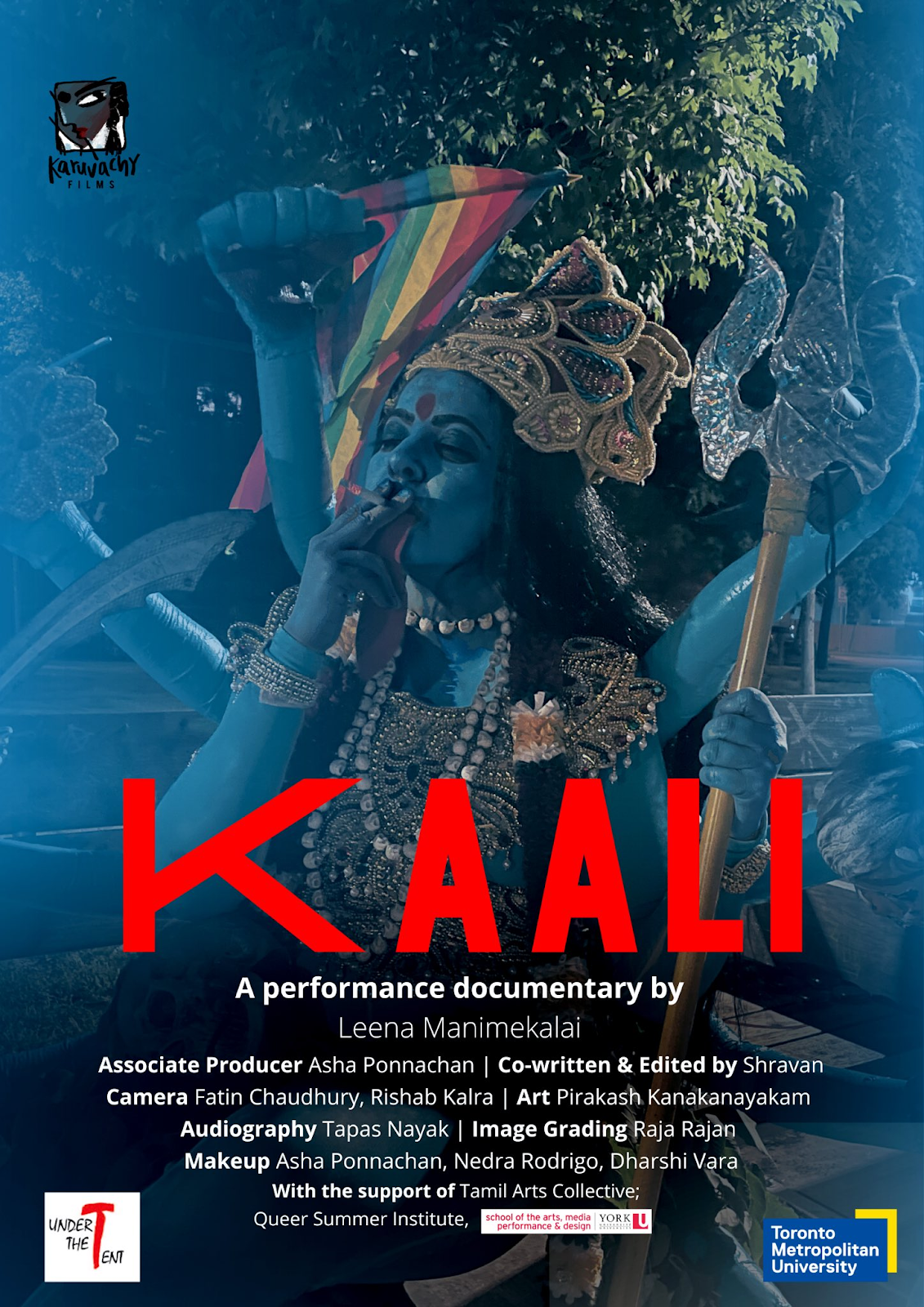

The controversial poster of Kaali (2022)

Your Kaali rattled the subcontinent. Can you explain how Kaali, a tribal goddess from rural India, fits in the narrative of exploring settler colonialism in the streets of Toronto?

I invite you to watch the film to reflect on it. In my film Kaali, Goddess Kali descends upon me and loiters in this stolen land that is also home for millions of broken people. It is a playful 9 minutes of an indigenous feminine spirit’s gaze and the returning gaze of people of various ethnic-racial-cultural backgrounds and nationalities. Sharing a smoke in the film is all about sharing humanity. It is not everyone but brahmanical patriarchal fundamentalists who were rattled. If I had portrayed Kali as their “Ma” changing their diapers they wouldn't have rattled.

Kaali is also my commentary on how multiculturalism is maintained like a zoo in Canada. One should not forget that this country is run by "white" power where immigration is open to people who are vanquished because the country needs human resources for nation building. The only difference between American imperialism and Canadian Capitalism is gun culture and an inclination towards welfare in terms of governance.

Institutions like Toronto Metropolitan University and Aga Khan Museum, though run by public money under Canadian sovereignty, dissociated themselves from me , the minute the Indian High Commission issued a statement to withdraw their support to my film. Economy that the Indian students bring to these institutions weigh more than academic freedom and they don't risk diplomatic relationships for that reason.

The tip of the iceberg is that North American Indians in power and positions are predominantly brahmins and stooges of hindutva but they play the victim card in the name of their colour and grab all the opportunities from historically oppressed indigenous, black and coloured populations. The institutions neither pretend nor put any effort to understand the complexities of Indianness or Tamilness but continue to posture diversity.

One of the biggest criticisms regarding Kaali, who’s seen smoking a cigarette and waving the pride flag on the film’s poster, was that you wanted to create a sensation. And that creative freedom, which comes with responsibility, was mishandled. What do you have to say about this?

This comes from the culture of victim blaming. It is no different from questioning a rape survivor on what clothes she was wearing. Always some senas or parivars or brigades will feel hurt whenever a film is out for public viewership. But democracy is not for the vigilantes to treat citizens as a flock of sheep. The Constitution of India protects the right to freedom of speech and expression to all the citizens of India. One must remember that the right to offend is also part of this freedom.

What happened in the case of Kaali is not a controversy, not a backlash, not an outrage. It was an organised campaign and orchestrated violence. This has been a pattern to the artists, activists, journalists, authors and dissenters who refuse to be part of the grand narrative of Hindu supremacy. It is so easy to blame an artist than the fascist forces who want to dehumanise and defile a living woman in the name of protecting the goddess.

“One thing I know for sure is that, nobody would have gotten to know the stories, if I had not filmed them” Leena

One of the biggest prices that you had to pay, due to the Kaali row, was that you were not able to be with your beloved grandma, Avva, during her last moments. Is the price that you pay for your voice, activism, social commentary and art, worth it?

I was severely traumatised, not being able to be with my Avva in her last days. I failed to hold my mother’s hands, grieve with her. I could not participate in the mourning with my family and folks. I will be scarred by this for my entire life. Nothing is worth this loss.

You’ve mentioned that you want audiences who view your films to enter the world that your films create and to participate in the narrative. But yet, independent films such as yours are quite inaccessible beyond festivals and limited availability on online platforms. What is the challenge here? Why aren’t such films widely available on mediums like YouTube under a pay wall?

Visibility has always been a huge challenge for indies. Filmmakers who refuse to provide ‘content’ for the market are invisibilized throughout history. Art is not a capitalistic commodity. A society should have a decency to appreciate, protect and nurture the art and the artist. Can't expect that from a society that censors, pirates and never values a cultural worker.

Leena filming தேவதைகள்/Goddesses (2008), a documentary that captures the story of 3 ordinary women (a fisherwoman, funeral singer and a grave-digger and) living extraordinary lives going against society’s norms to live and work according to the rules they have set for themselves

Financial success is not the primary driver of films such as yours. Yet financial pressures exist both professionally and personally. How does an artist like you reconcile this and still make the art you want?

Artists work, but never become workers. They are blood banks for vampiric institutions and an insatiable public expecting them to create magically without food, safety, home, help, time or money. My meditation during my Artist Residency at UofT would also be on how artists are forced to survive in the liminal space between precarity and resistance.

My independent work has never paid me for my labour. I pay my bills by doing commissioned projects for television, teaching, lectures and mentorship. I survive as a punctured space between one film to another.

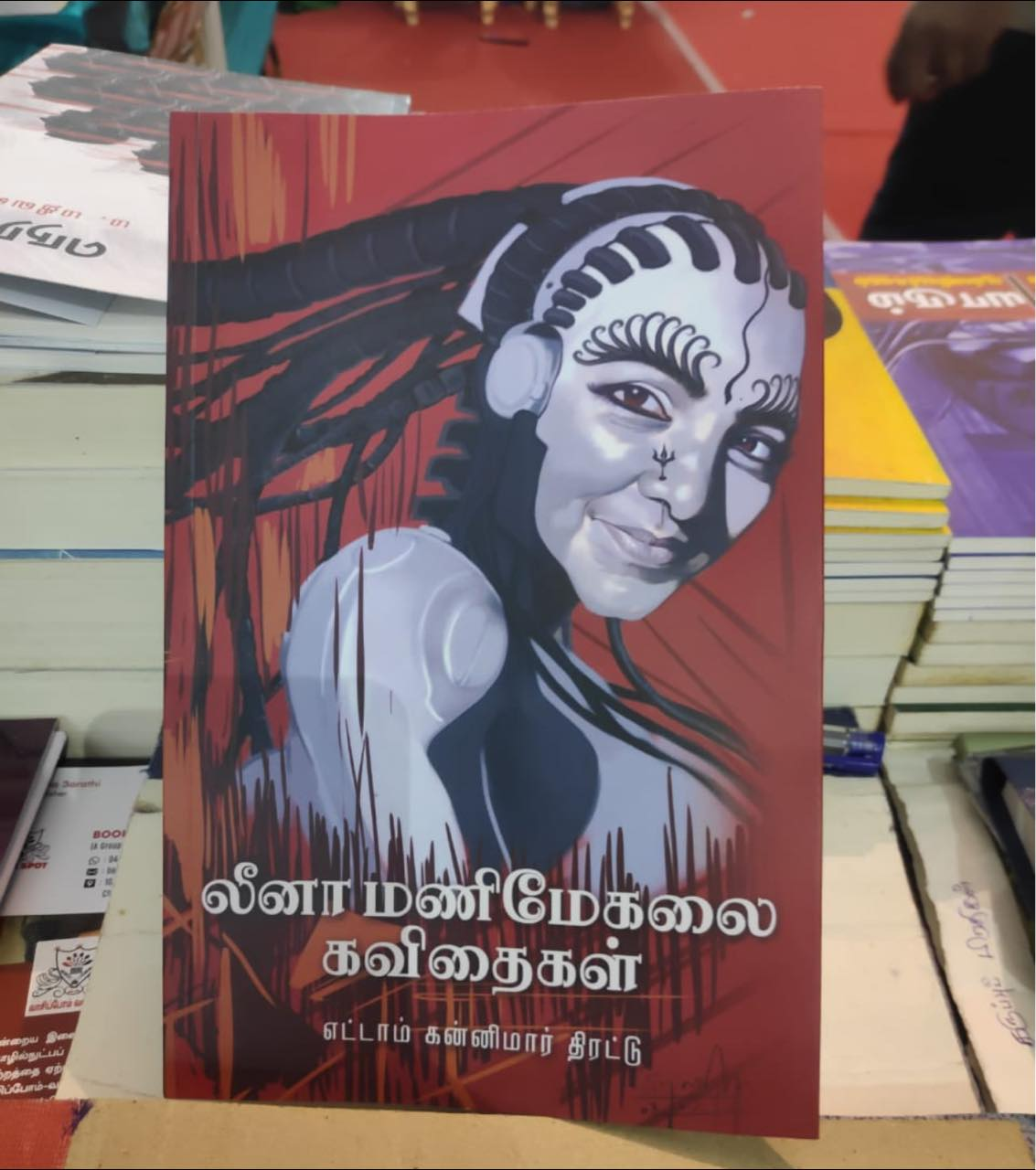

Leena’s collection of more than 500 Tamil poems was a crowd favorite at the recent 2023 Chennai Book Fair

To quickly touch upon your writing, is there anything that you are unable to express via your films that your poetry allows you to address?

I am formerly a Poet. My film practice is its extension. Both are world building exercises for me. I feel, I write, I create. I build my worlds with words, images, sounds, light, color, human bodies, landscape, wind, earth and every element of this Universe. My whole challenge is to translate my feelings to my unique world of poetry and cinema. I emote through my little creations.

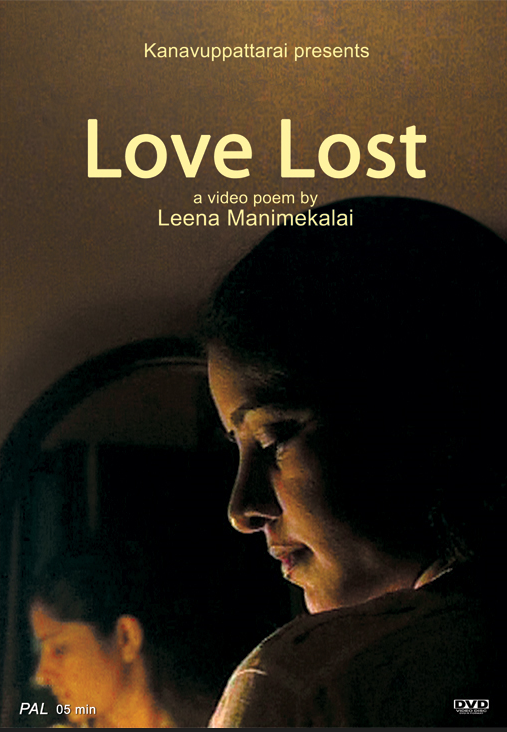

Cover from Leena’s poetry anthology தீர்ந்து போயிருந்த காதல் /Love Lost (2005). Excerpt from Love Lost available here

What’s next for you Leena and what are your goals with the Artist Residency at the University of Toronto?

It is indeed a huge honour to be named as Artist in Residence by University of Toronto. I am also an inaugural Artist in Residence of the Center of Free Expression at Toronto Metropolitan University. It is quite stimulating to interact with the scholarly interdisciplinary and artistic academic communities. So much to share, learn and unlearn. My days are packed with screenings, workshops, presentations, classroom interactions and debates.

My next is not in my hands. My multiple barrel gun is always fully loaded with feature film scripts, series, documentaries and transmedia projects. I leave it to the time fairy to trigger what and when.

“I went in my scooty wound with microphones to film my people. All I learnt is from them.” Leena

Scribbles:

A book that you are currently reading? The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwarz Bart

A book that changed your perspective? பதின்ம வயதில் வாசித்த, பெரியார் எழுதிய, பெண் ஏன் அடிமையானாள் (Penn en adimaiyanal by Periyar)

A film that you watched recently that you loved? Spellbound by Lucrecia Martel’s entire filmography, that I happened to watch while writing my thesis

Person(s) who’ve inspired you in your creative process? The characters and communities I happened to meet for my films. They were my Shamans

A film that you recommend for someone wanting to get into filmmaking? Surrender to the process, have faith and be the open vessel. Films will get made.

A line of poetry that has been stuck in your mind? அன்பின் வழியது உயிர்நிலை (Anbin valiyathu uyirnilai - Love is the basis of life, Thiruvalluvar)

Catch screenings of Leena’s Maadathy and Kaali on March 15, 2023 7pm at Innis Town Hall, Toronto. For more info visit: uoft.me/8QG

Works of Leena available online:

READ NEXT:

- myTamilDate Success: Agi’s First Attempt With Online Dating Led Her To Soulmate Ano

- myTamilDate.com Love Story: Suji & Sinthu Lived 15 Minutes Apart For Years And Never Met Until Joining MTD

- How France Met Canada: A MyTamilDate.com Love Story

- myTamilDate.com Love Story: Tharshi & Ravi Found Love During Lockdown