myTamilDate.com has been the most trusted dating community for single Tamils around the world for close to a decade! We’re the premiere dating site for diaspora Tamils and have the largest membership base in Canada, USA, UK & more.

Get to know our other success stories here.

____

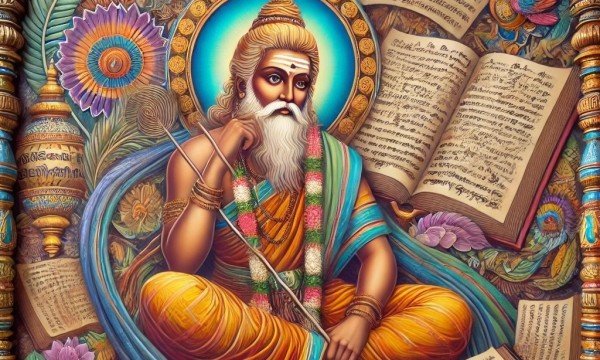

Parai means “To speak or to communicate”. It is also one of the earliest percussion instruments dating back to prehistoric times. Tholkaapiam, a Tamil grammar book written before the Christian era, mentions Parai as a standard musical instrument for many occasions.

Parai is a relic of anthropological remains of progressive human civilization. Initially, humans lived in the caves of hills as hunter-gatherers. Excess hide from the remains of carcass from hunting was experimented with for a percussion instrument, and Parai was invented.

In Sangam literature, there is enough evidence to point out Parai as an instrument of royal stature. It was performed in the royal courts of Sangam rulers. Devaram, the devotional hymns composed by highly revered Saiva saints on Lord Shiva around 6th century AD, has references to Parai being played inside the temple sanctum. It was only later called “Thappu” (meaning inauspicious) to derogate Tamil arts during the 14th century AD Vijayanagara rule of Tamil land.

In Adelaide, the Australian Tamil Arts Chief coordinator Lawrence Annathurai asked me to draft an essay on Parai as part of curriculum development for Parai Practice and Learning. Lawrence is a staunch supporter of Tamil arts and music. It is a kind of activity Australia never had before. He had a lot of difficulty in bringing up this art form to Australia due to the misconception and taboo attached to this musical art form. He had to undergo material and moral hazards due to his dedication for Tamil arts.

By the time this article was prepared, Lawrence and his team had performed in several Commonwealth of Australia Celebrations and trained about 15 people. We even travelled to Melbourne to train Tamil-Australian kids, and performed in their Pongal festival as an act of courtesy to expose this art form to the wider Tamil community.

Parai is already gaining greater acceptance in North America due to the coordinated efforts of the Federation of Tamil Sangams of North America (FeTNA) and professional parai trainers from Tamil Nadu. Thanks to the hard work of Lawrence Annathurai and his team Kayal Raj, Bala Murugesan and Robert Doss for pioneering this art form in Australia, the Tamils of Australia are catching up with North Americans, and the rest of the world will soon follow suit.

Keeping Australian Tamils and the international community in mind, this article is written after a brief period of research to give interesting information to novices and amateur Tamil historians. The idea of my writing is to shed some historical facts on this percussion instrument and to get rid of the taboos attached to the practitioner. This will help us reinvent this percussion instrument as a medium for the expression of freedom. It could also serve as a unifying force for the diverse Tamil diaspora.

Traditionally, the practitioner of Parai in India, especially among the Tamil community, is considered an outcast. This happened after the 14th century AD, when the Vijayanagara empire occupied the Tamils homeland. This practice of outcasts playing this art form gave birth to the English word “pariah”. As per the Cambridge dictionary, pariah means a person to be avoided. This English word had been taken by the British East India company to England by looking at the treatment the Parai practitioner of Tamil land received.

Let us look at the details of the making of this instrument. The frame of the instrument is made up of three arcs of neem wood (Azadirachta Indica), secured by metal fasteners to form a circle of about 35cm. The bull/cow’s neck hide is stretched over this wooden frame and glued by natural resin.

The percussion sticks used are two in number and named after the quality of the sound they generate. The thin slender percussion stick is called “sunddu kucchi” (high pitch) and the other thick relatively shorter stick is called “adi kucchi” (base note). The sunddu kucchi is about 28cm long and the adi kucchi is about 18cm long, usually made of bamboo.

The instrument needs to be warmed up under indirect heat before playing. The properly heated instrument can conduct sound up to 3km away. The practitioner can hold this instrument while standing and start the percussion. He is expected to dance while playing this instrument, with singing as an additional option.

Let us look at the stature enjoyed by the instrument in ancient times. Kurunthogai (Sangam literature from the 3rd century BC) refers to parai as an auspicious instrument to be played during marriage ceremonies of the ancient Tamils. Lord Shiva is often found dancing to Parai music near a graveyard (Karaikal Ammaiyar Hymns). In one such devaram (hymn) written by the highly revered Thirugnanasambantthan in his Thiru Nindravoor pathigam, it is said to have played inside the temple along with a blowing conch.

In one devaram, Lord Shiva is referred as “Paraikolpaaniyar & Piraikolsenniyar” meaning Shiva holding a Parai and wearing a Pirai (crescent) on his head. In many temples of Tamil Nadu, sculptures are engraved showcasing Parai playing and girls dancing. The once glorious status enjoyed by this instrument was reduced to funeral music only after the Vijayanagara invaded the Tamils’ country.

Parai was also used for multiple other reasons, like warning people about an upcoming battle, requesting civilians to leave the battlefield, announcing victory or defeat, stopping a breach of water body, gathering farmers for farming activities, warning wild animals about people's presence, as well as percussion during festivals, weddings, celebrations, worship of nature and so forth. Its other uses included to announce the King’s proclamations, and to communicate information from one place to another by playing codified notes for a purpose.

In current times, Parai is considered a musical art to express freedom. It is a very attractive and active art form combining dance, percussion and singing.

The Tamil diaspora is embracing this instrument as a mark of their liberation. It is common people’s music, so there are no boundaries to contain freedom of expression. It is an emerging popular form of art among the Tamil diaspora. It is unique and has great values in unifying the Tamil diaspora.

- Dr. Prem Shanmugam

Canada

Canada