myTamilDate.com has been the most trusted dating community for single Tamils around the world for close to a decade! We’re the premiere dating site for diaspora Tamils and have the largest membership base in Canada, USA, UK & more.

Get to know our other success stories here.

____

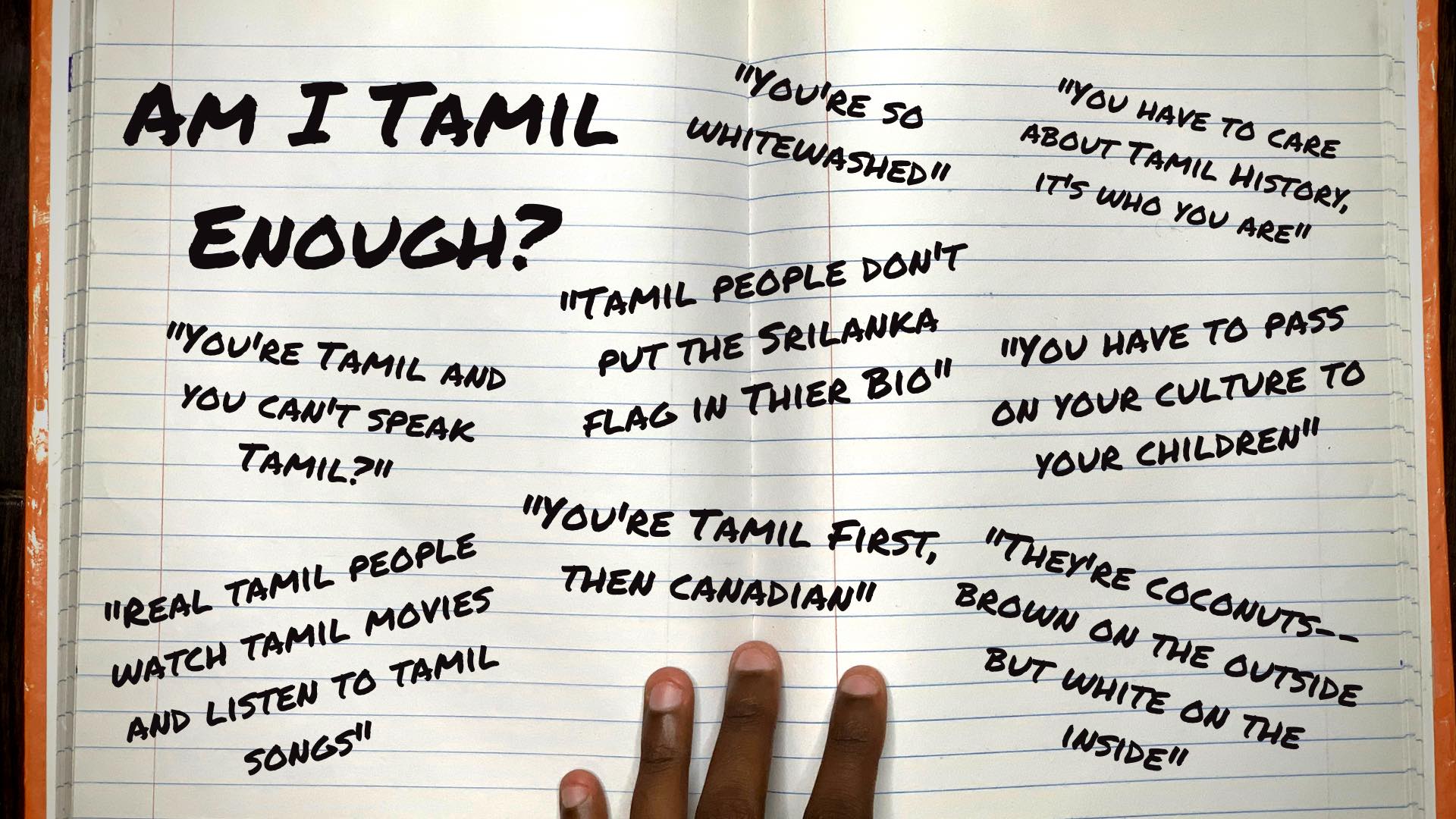

The recent discussions around the Peel District School Board’s comments regarding Mullivaikal remembrance day has led to very heated debates and set firm expectations of how real Tamils are supposed to respond. Tamils are expected to speak up and join the debate, even those who do not have a full understanding of what they are speaking up for. These expectations, and the backlash against those who do not meet them, are one example of the broader divisions that exist between Tamils in the diaspora.

“How can you not care? You’re Tamil!”

“What? How can you not like Tamil music?”

“You don’t speak Tamil? Really?”

If you have ever heard or said any of these things, you may have an idea of what I am referring to. In my experience, these are among some of the many factors used to determine “how Tamil” you are. There is a certain level of pride in being able to speak the language fluently, knowing how to play a classical Tamil instrument, or simply in being Tamil, which are all good reasons to feel pride. But why is there often a certain disdain for those who do not do these things?

For many in the diaspora, identifying as “Tamil” becomes a stronger draw than either Sri Lankan or Canadian. Growing up, you were never “Sri Lankan,” since wartime nationalism made a clear distinction between Tamils and Sinhalese, and your parents made it clear which side you were on. Many aspects of Canadian culture, whether they be partying, a career outside medicine, dating, or having friends of the opposite sex were barely comprehensible to most parents, who came here from a country where these things were difficult, impractical, or forbidden. Witnessing “Canadian-ness” in school and in the media while surrounded by traditional Tamil influences made it very difficult to understand how to interpret the differences between the two cultures, and which camp you belonged in.

Caught between the two, you could not fully shed the “Tamil-ness” you were raised to value. You were always Tamil first, regardless of your opinions on this matter, and the war in Sri Lanka pushed the idea that being Tamil was something important that was under threat, that should be treasured and guarded. Growing up I saw the many ways young people chose to display their inherent Tamil-ness. Back in the day, guys were quick to put on Tamil Tiger bandanas, t-shirts, dog tags and belt buckles without having much of an understanding about the origins of the war or what the LTTE’s goals were. Others instinctively claimed they disliked Sinhala people because “they did bad things to us” without being able to give any specific explanation for why they felt that way. Tiger or “proud Tamizhan” tattoos were also common. Many of the people I encountered who most vocally claimed to enjoy Tamil music often did not speak Tamil, nor did they fully understand what the songs were about. But holding these views became measures of how Tamil you were, and a “good” Tamil did not go against them. Those who did became the “fake” or “whitewashed” Tamils, a mindset that I also used to have.

My interpretation of this division is the difficulty in establishing a clear identity. I have always felt at home in Canada, that is not the issue. But what exactly does being Canadian mean? Especially being the very first generation, it is hard to determine what specifically makes me Canadian other than my passport. Progressiveness and tolerance can be applied to hundreds of identities, not just Canadians, and there was never any pan-Canadian unifying factor that provided a means to relate to all the people I met here. Identifying as Tamil, however, provided a pretty clear blueprint for acceptance - you have one language, a shared history and culture amongst your people of uprooting and resettling; a history and culture that, according to many people around you, was also under threat and needed saving. But as Tamils, many of us are raised to value and be proud of a culture that we may want to belong to, but know very little about. For example, my parents did not really push religion, Tamil pride or politics on me, though I did come to love Tamil music and speak the language fluently. But I found myself intrigued by religion, by the civil war, and the aspects of the culture I felt I had missed out on, because understanding these aspects became key to understanding the only identity I felt I could realistically attain. Trying to “be Tamil” became a conscious effort rather than being something I was by birth, and I noticed similar attitudes in people around me: preaching Tamil identity and values, while viewing any unwillingness to conform as an unwillingness to “be Tamil”.

As I tried to understand these aspects, I came to realise that Tamil identity within the diaspora will only diminish more with each new generation, something that bothered me; the language will become unfamiliar, and all the aspects of the culture that so many people I know try to understand would lose its relevance to children who are born and raised further removed from its influences. Once I realised this, those who did not value their Tamil identity as I did or were not as immersed as I was in learning about Tamil culture somehow became “inauthentic.”

Since then I have learned how inaccurate that mindset was, and met many friends whose identities are influenced by different experiences. With some I discuss Tamil music, politics and history; with those who did not relate to these themes, it did not take anything away from my ability to relate to them. Very few of my friends today actually share my level of interest in Tamil history or culture. I have long since learned that being Tamil has very little to do with your willingness or unwillingness to embrace the many aspects of Tamil culture; it is something you are by birth, and does not diminish regardless of how you choose to carry or value it. No one has to prove how Tamil they are. People’s identities are shaped by experiences, and their values and priorities are not always going to line up with your own. This applies just as much to the recent genocide debates, and the many other aspects of Tamil identity. Some are passionately vocal, some are unaware and some do not care. They are all Tamil.

The more you open up the narrow confines of your Tamil identity, the more you will find in common with those around you, whether it be a proud Tamil, a Tamil who simply likes Tamil music, all the way to the person born Tamil who does not feel as connected to the culture. If your goal is truly to stand for Tamil identity and Tamil people, you must stand for all of them, not just the ones who agree with you.

**Looking to create your love story? Join the other couples who have dated and married through myTamilDate.com!**

"myTamilDate Love Story: Jenani & Nav Found Each Other At The Right Time And Right Place In Life"

"myTamilDate.com Love Story: Tharshi & Ravi Found Love During Lockdown"

"How France Met Canada: A MyTamilDate.com Love Story"

***CLICK HERE to listen to us on Spotify!***