A couple of years ago I was with my family and some family friends on a trip to Newfoundland. We were touring an old fort and my dad made a comment to the effect that it was interesting how we come to see tourist attractions like this but we do not take interest in the history and culture of our own people. Hearing this, one of the guys that came with us, a fifty-something year-old Tamil man, took a look around and said, “if it wasn’t for colonialism we’d all still be squatting in the gutters in our loincloths.” A couple of security guards started eyeing us nervously at the intensity with which we all yelled at him, and made the rest of the trip a little awkward.

For me, it was a reminder of the way many of us and those around us think: that Tamils, our culture, values and ways of living are somewhat backwards and primitive; that colonisation, despite its negatives, lifted us out of our ways and brought us into the liberating world of gender rights, women’s empowerment and tolerance for all; and that our ancestral homelands still can’t ‘get it together,’ decades after independence. The irony, however, is that the countries and cultures that we look to as refreshing models of tolerance, stability and progressiveness are the very cultures that took these values away from Tamil communities, reinforced existing issues, and created the lasting damage that explains, in part, why a quarter of all Sri Lankan Tamils do not live in Sri Lanka, but in Canada, Australia, the UK, France, Malaysia, Réunion and elsewhere.

This is not a denial of the part we play in perpetuating issues we have in our communities. As Tamils, we have many, and we all know people who have struggled through its many toxic, misogynistic, and self-destructive elements, some of which I will address. There is a lot of work to be done, and that responsibility lies only on us. But understanding the historical injustices that have sabotaged progress in the Tamil community, and influenced our ongoing issues is one step towards ensuring that we make informed judgements, and do not run away from our own identities and communities.

The war, gender norms and fair skin

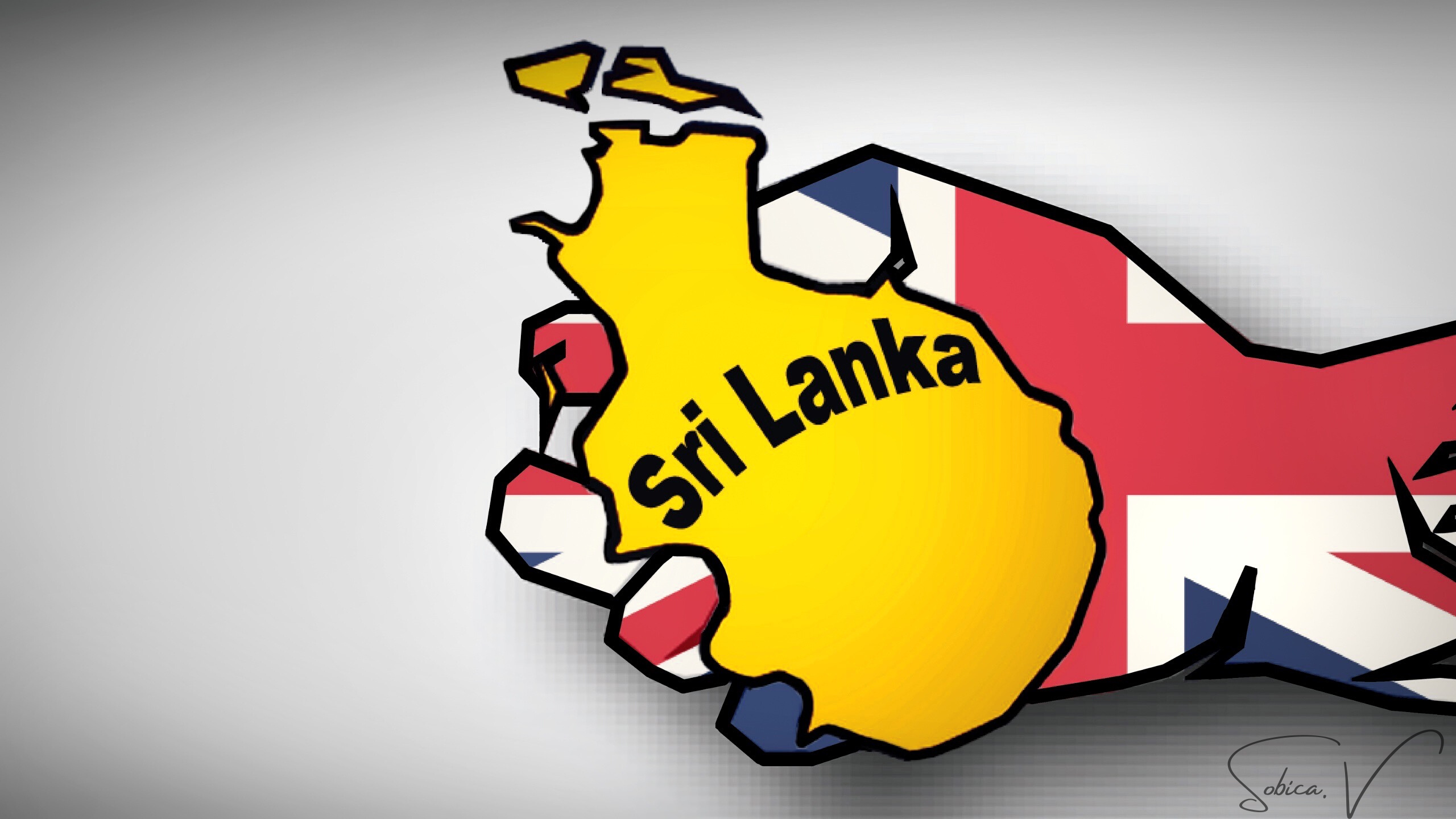

The war in Sri Lanka, which killed thousands of our own relatives and created long-lasting hatred between Tamils and Sinhalese, has roots in colonial policies. Divisions have always existed between Tamils and Sinhalese, but were mostly geographical before colonisation; according to Syed Soherwordi, a conflict studies expert at the University of Edinburg, the British encouraged ethnic division in order to make ruling easier, merging Sri Lanka’s various kingdoms into strict Tamil and Sinhala blocks, and encouraging the creation of nationalist identities. They imported thousands of Indian Tamils into the country as cheap labour and provided Tamils with preferential positions in civil service, causing anger within Sinhala communities.

Our obsession with fair skin is also a result of these policies. While lighter-skinned and darker-skinned people have always existed in Sri Lanka, it was the colonial administration that created a race-based social hierarchy (to fit Britain’s own class-based system) that benefitted lighter-skinned individuals the most, and established skin colour as a determinant in people’s ability to succeed. Soherwordi states that neither the Tamil or Sinhalese languages had a word for “race” before this time: this was a British concept, and the systems of governance that they created forced these newly established races to compete against one another for services, causing further resentment. As decades passed, governance through race-based policies became the norm. The anger and strict ethnic divisions created as a result of colonialism directly influenced race-based competition, distrust and the hardening of ethnic identities. Upon independence, the marginalised Sinhala majority re-emerged and reversed the preferential position that Tamils held, establishing Sinhala as the only official language, and repressed Tamils’ abilities to meet employment and educational requirements, which in turn led to the growth of Tamil protests, militancy, anti-Tamil riots, massacres and all-out war. These ethnic divisions did not exist before colonisation, but were created during its course (Soherwordi, 2010).

Our mostly binary perceptions on gender identity are another colonial import. Scholars such as Amy Bhatt, a gender and women’s studies researcher, have pointed out that same-sex relationships, gender fluidity and third genders are central to ancient Hindu scripts, stories and poetry; the religious deities that many Hindus continue to worship today are often gender fluid, such as the androgynous male-female Ardhanarishvara (Bhatt). It was Britain that outlawed homosexuality in India and Sri Lanka in the mid-1800s because of Victorian ideals of strict male and female identities and ‘immoral’ sexual behaviour. The legalisation of homosexuality in India in 2018 was not India finally catching up to western moral standards, but a reversal of colonial policy. Sri Lanka’s Penal Code of 1883 still criminalises same-sex relations as “unnatural offences” and “against the order of nature” — you can probably hear the Christian religious undertones, while the year of the Penal Code’s inception makes it pretty clear who implemented it (Human Dignity Trust).

Governance

In the 1700s, immediately before the British arrived in India, India was the richest country in the world (The Economist). While India was richer upon independence than it was at the beginning of colonisation, this was mainly due to the country’s population growth between the 1700s and 1940s (Forbes, 2017). A study by the economist Utsa Patnaik found that during its time in India, Britain stole just under 45 trillion dollars from the country, through policies such as paying Indian merchants with their own previously collected tax money, and a host of other scams. Today, this value is 17 times the size of Britain’s economy, and would undoubtedly bankrupt the country many times over if it were to pay it back. While scholars point to railways and democracy as positive British influences in India and Sri Lanka, these were created for purely colonial administrative purposes, and do little to justify the destruction of traditional ways of life, famines that killed millions, and the creation of Sinhala-Tamil and Hindu-Muslim tensions that have killed millions more throughout Sri Lankan and Indian history.

Have you ever wondered what is wrong with our ways and thoughts, or why we can’t seem to ‘get it together’? As said by Nelson Mandela upon the end of apartheid, “The truth is that we are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed;” Tamils, at least in the diaspora, have achieved the right not to be oppressed, but the legacy of the systems set in place to keep them in check, and the resulting social issues and political corruption did not go anywhere upon independence in 1947 and 1948; while direct colonial oppression arguably ended upon independence, it did not bring freedom from its aftereffects. This sequence of events is just as applicable to the history of Rwandans, Syrians, Canada’s indigenous communities, the African slave trade and the long-lasting effects of colonisation in dozens of countries, and is why generational oppression has such long lasting and destructive social consequences.

This is obviously a very short overview of only the most prominent themes, and requires a much deeper dive to be comprehensive. It probably sounds like I am blaming everything on colonialism; does all this mean that if colonisation had not occurred, Sri Lanka and India today would be havens of tolerance, stability and LGBTQ rights? Or that Sri Lankans and Indians enjoyed perfect equality and prosperity before colonisation? Of course not. We cannot say for sure how history and these social issues would have played out. There are many issues in our communities, some of which we created, some of which we did not. However, the many aspects of our culture that many of us dislike so much and want to change are products of colonisation, or were made worse by colonisation. And the Sinhalese population, like Tamils, are another victim of this history.

This history does not excuse the crimes committed by either side during the war, nor is this a call to simply direct all our anger towards Britain. It is pointless and self-destructive. Simply being angry is not going to change history, and is more likely to lead to defensiveness and division rather than understanding and dialogue. Blaming everything on the past can be dangerous, since it puts the responsibility for fixing it on someone else. I am only encouraging us to educate ourselves. As Tamils, we have a responsibility to address the problems that exist in our community; caste and colour obsession, patriarchy, emotional repression and destructive coping mechanisms that have created long-lasting damage to families are just some of them. We can look at our culture and these challenges as something to shun or run away from, like that family friend of mine in Newfoundland did, or we can educate ourselves and confront them. Awareness of how these problems came to be in the first place is the first step towards breaking generational thought patterns and behaviours.

Al-Jazeera. (2018). How Britain stole $45 trillion from India. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/britain-stole-45-trillion-india-181206124830851.html#:~:text=Drawing%20on%20nearly%20two%20centuries,It's%20a%20staggering%20sum.

Bhatt, A. India’s sodomy ban, now ruled illegal, was a British colonial legacy. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/indias-sodomy-ban-now-ruled-illegal-was-a-british-colonial-legacy-103052

Forbes, 2017. The British Left India Richer Than They Found It - Unfortunately It Was Malthusian Growth. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/timworstall/2017/08/15/the-british-left-india-richer-than-they-found-it-unfortunately-it-was-malthusian-growth/#741cf86b5a8f

Human Dignity Trust. Sri Lanka. Retrieved from https://www.humandignitytrust.org/country-profile/sri-lanka/

McQuade, J. Colonialism was a disaster and the facts prove it. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/colonialism-was-a-disaster-and-the-facts-prove-it-84496#:~:text=During%20the%20heyday%20of%20British,per%20cent%2C%20or%2027%20years.

Soherwordi, S.H.S. (2010). Construction of Tamil and Sinhalese Identities in Contemporary Sri Lanka. Pakistan Horizon, 63(3), 29-49.

The Economist. (2014). World’s biggest economies through history. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q_vJfIy1wpw