There is an ongoing sentiment today to shame the younger generation for their lack of fluency in the Tamil language and adherence to Tamil culture. In recent years, Tamil youth have been subject to accusations that their language shortcomings are a result of contempt towards their heritage.

However, the surge of youth-led Tamil Student Associations in high schools and university campuses across Canada demonstrates otherwise. I would argue that many Tamil youth today are far more motivated to learn Tamil than their parents are to teach it to them. The inability of Tamil youth to speak, read and write proficiently in the Tamil language reflects a broken education system they had no part in developing. To blame Tamil students rather than analyze the systemic roots of this issue is both lazy and irresponsible.

Since the age of 5, I was pushed by my parents to attend Tamil class. As nerdy as it sounds, I looked forward to it. I thoroughly enjoyed reading and writing, learning about the history of my community and discovering my culture.

For several years, I attended two Tamil classes weekly. In high school, my Saturday afternoons were spent attending a four hour long Tamil credit course program every week, alongside a private tutoring session on Sunday mornings.

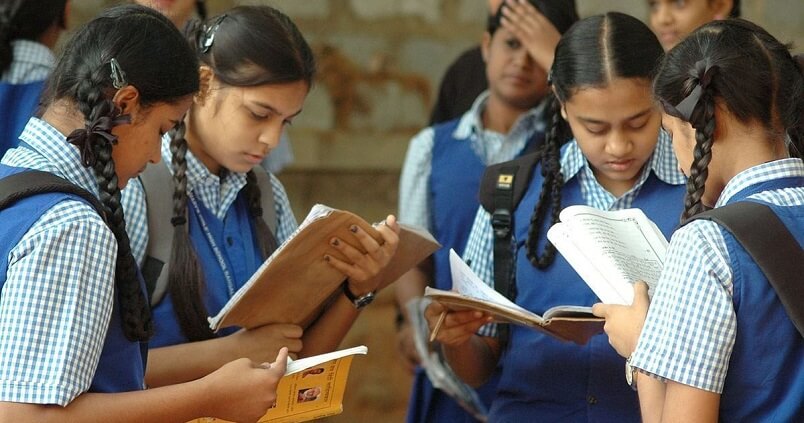

Operated by local school boards, international language courses are available for high school students as means to gain a supplementary credit in a foreign language of their choice. Often, this credit becomes a vital mark-booster as it may be counted towards the admissions average for certain post-secondary programs. Many Tamil youth enroll in extra-credit Tamil language courses for this reason. Consequently, international language programs, much like private schools, have gained a reputation among post-secondary institutions for acting as credit mills.

This state of affairs has rightfully been blamed on students and parents for their mark-oriented aspirations. Tamil educators have been criticized for turning the other cheek during instances of cheating or for handing out undeserved marks. Tamil school administrators should be held accountable for the transformation of classes into credit mills as their curriculum and conservative methods of discipline have failed to inspire Tamil youth.

As much as I have come to appreciate the breadth of knowledge and skills I’ve gained through Tamil class, it is undeniable that this institution needs to modernize. Historically, any culture, religion, or ideology which refuses to evolve is doomed to die out. Tamil culture is progressing alongside the needs and learning skills of Tamil children. Yet the content and knowledge prescribed by Tamil classes have barely advanced.

My love-hate relationship with Tamil class has motivated me to write this piece, through which I will outline a few of my many vexes with it.

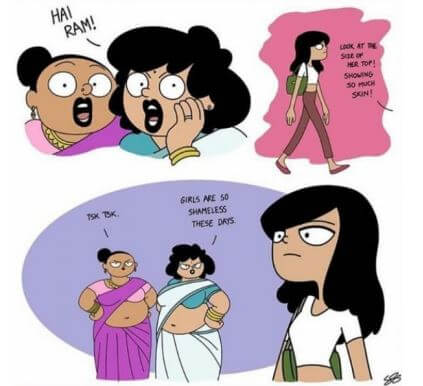

The Dress Code

One of my concerns regarding Tamil class are unnecessary rules and regulations, particularly ones pertaining to dress code. Tamil boys who choose to low-ride are often treated as delinquents and publicly shamed by educators. Similarly, Tamil girls wearing ripped jeans have been mocked with painfully overused “uncle” jokes.

Using security and uniformity as a veil, many Tamil credit courses have enacted strict dress codes. Some even require students to wear a uniform to class. These dress codes exist for one reason alone – to reinforce the existing perception that dress style correlates with character. The judgmental root of dress codes is to be expected considering our community’s ongoing issues with prejudice.

I continue to question how these administrations believe that by dictating the clothing choices of Tamil youth, generally unmotivated students will not treat it as a deterrent from attending class. My former credit course justified the mandatory uniforms by explaining that they were in place for school hall monitors to identify us as Tamil class attendees. It is as if a simple ID card or name tag wouldn’t have sufficed.

I may have believed this faulty rationale if not for the countless patronizing comments I’ve heard staff direct towards students for their clothing. It is clearly evident that the underlying reason for a dress code is to ensure modest and “decent” dressing.

Additionally, enforcing a dress code extracts from the limited time available to learn, and is surely not something already overwhelmed teachers should or want to be tasked with. Regardless of your personal views on this matter, imposing a dress code on youth who thrive on freedom of expression and individuality is not effective in achieving what should be the overarching goal of Tamil classes - to raise self-motivated youth with a genuine love for and pride in their native language and culture.

The Propagation of Regressive Ideologies

I don’t think there has been a single year in Tamil class where the workbook hasn’t included an entire unit on manam (honour). Historically, manam continues to be revered as one of the pillars of Tamil culture and a fundamental component of Tamil identity. To my dismay, Thirukkural, one of the most progressive pieces of Tamil literature, has spoken extensively of the significance of honour to common men.

உயிர்நீப்பர் மானம் வரின் (969)

The above-mentioned kural essentially says that truly noble men will not hesitate to commit suicide when dishonor has befallen them, much like the wild ox that kills itself when one of its hairs has fallen.

Even as this kural explicitly glorifies suicide, Tamil classes wield it as a tool to advance their toxic narratives. Children’s workbooks include entire chapters dedicated to narrating the death of Chera king Kanaikal Irumporai. Educators fondly recollect his “valiant” act of killing himself after losing a battle to his sworn enemy.

Being subject to these teachings led me to think of all the occurrences that may strip a Tamil of their honour. Going to college instead of university? A survivor of sexual assault? Pregnant out of wedlock? According to the regressive beliefs spouted by Tamil classes, if any of these situations apply to you, you’re better off killing yourself than persevering.

It’s astonishing that not one Tamil educator I’ve encountered has condemned the pervasive notion in our community that it is more noble to commit suicide than to live without honour. It’s particularly baffling when taking into consideration how often individuals lose their “honour” for harmless personal choices or situations over which they have no control. To know that these backward attitudes are being instilled in Tamil children rather than qualities like resilience or self-respect is concerning to say the least. We live in a community in which manam is prioritized above all, and to preserve it is purported to be a Tamil’s principle obligation. By the same token, Tamils often react to suicide by labelling the individual behind the act as selfish. The irony is sickening.

Mixing Religion With Language and Culture

There are Tamil Hindus. There are Tamil Muslims. There are Tamil Catholics. And there are Tamil atheists. So why exactly do Tamil classes continue to conflate religion with culture?

Periyar E.V. Ramasamy is among the most influential Tamil activists in history. He is also the least mentioned in curriculums. He was an outspoken critic of caste and patriarchy, but is uniquely renowned for his disdain towards organized religion. He vehemently opposed both Hinduism and Catholicism, believing that Hinduism serves simply to reinforce Brahmanic supremacy and the inferiority of Dalits. Because of his vigorous campaigns, lower caste communities like Dalits were finally allowed entry into temples.

As a legendary reformist, he should be hailed by the Tamil community for his social justice advocacy. Yet it appears that the very anti-establishment philosophies he espoused is the reason he is rarely spoken of. In comparison to other historic Tamil figures, rarely do Tamil classes discuss his legacy. Blacking out the histories of activists like Periyar is no different from the whitewashing of history that takes place in North American schools.

Tamil classes should also be more accommodating towards those of all faiths and spiritual leanings. Instead, workbooks often spend an inordinate amount of time discussing insignificant details about temples, mythologies and Hindu customs. Of course, I acknowledge the historical significance of temples to Tamils and the interconnected nature of Tamil culture and Hinduism. Even so, I’d assert that a secular education system may be the way forward to pass on our language and culture to modern Tamil youth, many of whom may not be of faith. The time teachers devote towards kurals emphasizing the significance of God to one’s life could be better used to analyze universal kurals concerning philanthropy.

___________________________________________________________

Truth be told, as much as I’ve criticized Tamil second-language classes throughout this entire piece, I’d like to emphasize how much respect and admiration I hold towards Tamil teachers. With families of their own to take care of, these teachers put their all into their work. While often rewarded with low wages and essentially non-existent benefits, Tamil teachers are unfairly tasked with getting through entire curriculums within a few hours, managing large class sizes comprised of students with varying skill sets and training classes for annual performances, all while taking it upon themselves to raise students to be socially-active contributors to society.

Tamil educators have been at the forefront of this movement, rallying for a reform in the second-language education system offered to Canadian-born youth. One of my former Tamil teachers recalled a town hall in which she apparently irritated members of the administration. They complained that she always took the side of students. She rightfully asks, “as a teacher, isn’t that my job? If not working in par with students’ interests, who else?”

With that sentiment in mind, we should collectively work towards reforming the model of education we provide to incoming generations of Tamil children. Such a feat can only be accomplished through greater and more diverse dialogue.

வாழ்க தமிழ் மொழி Related articles: A Look Back at My Experiences at Tamil Tuition Class Learning Tamil as an Adult Tamil Language Schools On the Rise in United States Is Tamil Going Extinct? Back To Tamil Class