___

***Are you or someone you know in the global Tamil community doing great things? We'd love to feature them: FILL OUT THIS FORM ***

Network & collaborate with Tamil Changemakers from around the world. Request to join our private LinkedIn community here.

___

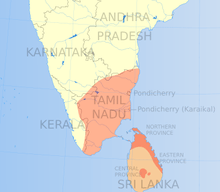

The Tamil homeland (தமிழகம்) is found in modern day South India (தென் இந்தியா) and Sri Lanka (இலங்கை); however, the Tamil society today is made up of a multi-national people, with a wide diaspora forming significant communities in 30-60 countries across the world[1]. Reasons for the emigration from the Tamil homeland include the spread of the Tamil empires in ancient times, business and work opportunities during the medieval period and indentured servitude during the European colonial periods. Because of these waves of emigration, Tamils are found in practically every part of the world, including North America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Australia and other parts of Asia. There are some cases where the Tamils have assimilated and integrated into their adoptive countries and others where the Tamils have formed a new community while retaining their language and cultural practices from the Tamil homeland[2]. With the success and challenges faced by the Tamils living and thriving in the countries that may now be called their home, the Tamil people have evolved into a diverse community, integrating traditions and practices that are new while retaining the traditions coming from the Tamil homeland, all of which is in constant evolution.

One significant reason for the diaspora’s existence today is the mass exodus that took place following Black July (கறுப்பு யூலை) in 1983, resulting in the start of the Sri Lankan Civil War[3]. While this event is attributed as the single cause for the exodus of hundreds of thousands of Tamils from Sri Lanka to different parts of the world[4], I believe that this has resulted in a culmination of many other events throughout the history of Sri Lanka and its continued impact on the Sri Lankan Tamil people (இலங்கை தமிழர்). I’ll be writing a series of articles exploring my thoughts on the many factors that have contributed to the Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora (புலம்பெயர் இலங்கை தமிழர்). The factor that I’ll be focusing on here stems from Sri Lanka, then Ceylon (சிலோன்), gaining independence from the British Empire.

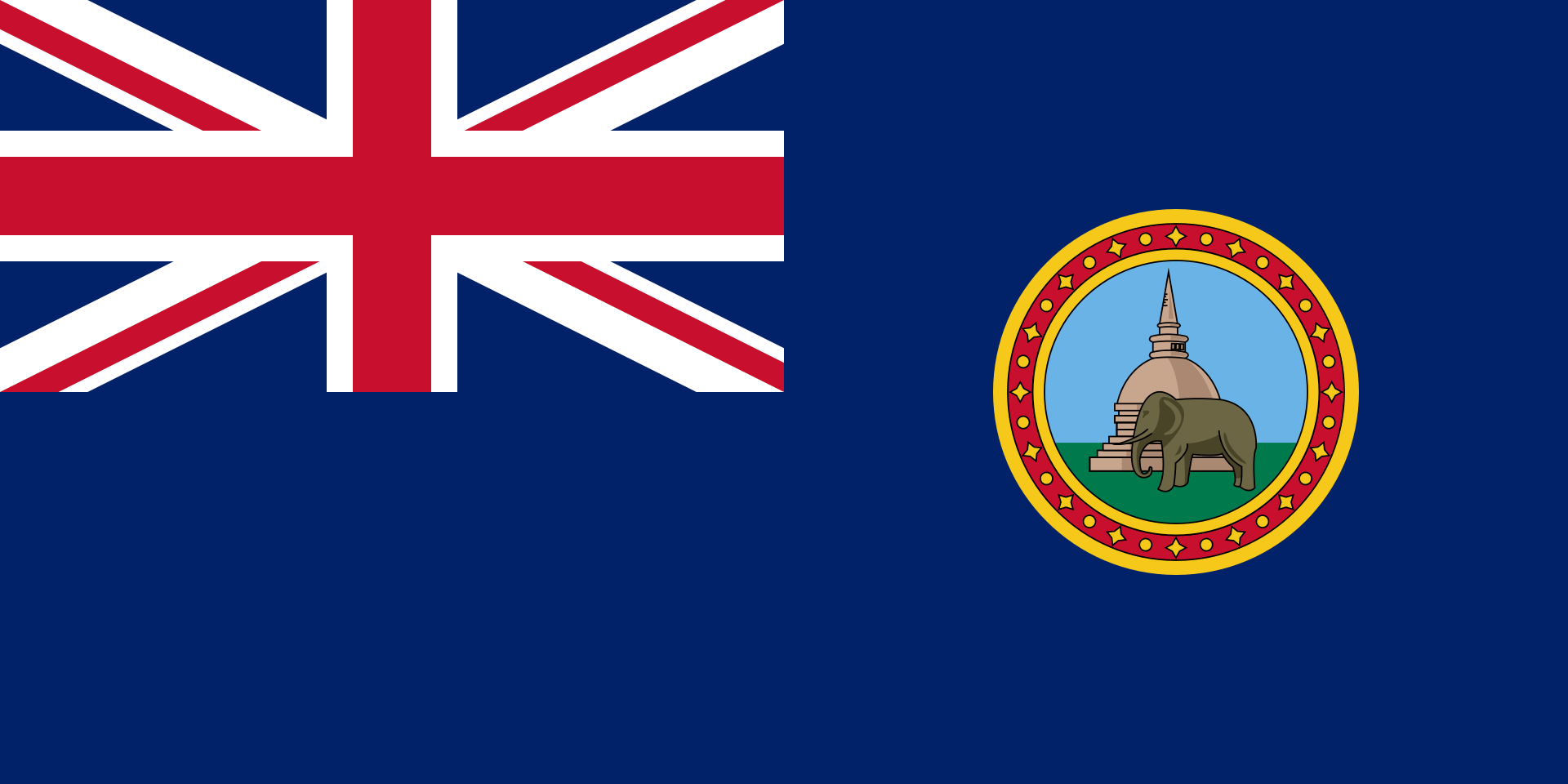

Sri Lankan Independence Day (இலங்கையின் தேசிய தினம்) took place on February 4, 1948 and has been commemorated annually ever since. Independence Day marks the start of self-rule in Sri Lanka with a peaceful transfer of power between British representatives and Ceylon representatives, marking the end of nearly four centuries of colonial rule by foreign European powers and the start of a nation being truly governed by its own people[5]. The first government to rule the independent nation was a coalition headed by the United National Party (ஐக்கிய தேசியக் கட்சி) with support from the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (அகில இலங்கைத் தமிழ்க் காங்கிரஸ்). D.S. Senanayake became the nation’s first president with support from the leader of the Tamil Congress, G.G. Ponnambalam (ஜி. ஜி. பொன்னம்பலம்).

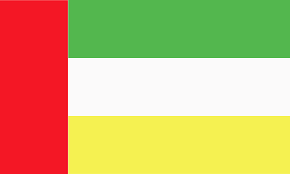

Flag of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress

Flag of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress

If there was some presence and support from the Tamils politically when the transfer of power for an independent Sri Lanka took place, were the Tamils in favour of this independent nation and was it a part of their identity? I don’t believe that there is a straightforward explanation; however, I do believe that the rise of Tamil nationalism started in parallel with the events leading up to independence. I also believe that the two factors contributing to this Tamil nationalism include the introduction of Christianity and the political representation of the Tamils before and at independence. These factors set the tone for what would unfold in an independent Sri Lanka and the sense of a separate identity for the Tamils within this nation.

The colonial period was when Tamil nationalism in Sri Lanka originally started. As the Europeans established their presence, missionaries came in to convert the Tamils to the Christian faith, namely towards the Catholic, Anglican and Methodist denominations. This sparked the revival and preservation of Hinduism since the entrenchment of Christianity was seen as a threat to the Tamil identity[6]. A common cultural, religious and linguistic sense of community was established through the construction of Hindu schools, temples and societies to counteract the European missionaries and their attempts to Christianize the local population[7]. The establishment of this identity was crucial in the political realm as it contributed towards making the Tamil presence known and cemented in what was then called the Dominion of Ceylon under British rule.

In the nineteenth century, the British had taken control of and unified the entire island[8]. At this time, an advisory council was established for governing the island. This council was composed of three Europeans and one member from each of the Sinhala, Tamil and Burgher communities[9]. This was changed to communal representation in 1919, whereby seats are divided on a communal basis for the entire system of representation[10]. Since the Sinhalese outnumbered the Tamils, the first election under the communal representation model resulted in the Tamils only winning three of the thirteen seats contested[11]. Starting in the 1920s, the Tamils viewed themselves as a minority community. Under the communal representation model, the Tamils further delved into developing the sense of a Tamil national identity and determined to protect their interests at all times[12]. This has resulted in the establishment of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress led by G.G. Ponnambalam. Even during the times of colonialism, a uniquely Tamil sense of nationalism was forming instead of forming a common identity among the other ethnic groups on the island.

____

____

The sense of a separate Tamil identity was further cemented with the electoral reforms in 1931 following findings from the Donoughmore Commission (டொனமூர் ஆணைக்குழு), resulting in the Donoughmore Constitution (டொனமூர் அரசியலமைப்பு) which lasted until 1947. The Commission eliminated communal representation and proposed universal franchise, where representation was proportionate to the population[13]. It also created a check and balance system for every government department whereby all ethnic groups gained something, though the British appointed governor of Ceylon was given veto power abilities[14]. Both the Tamil and Sinhala communities for different reasons opposed this form of government. The Tamils realized that proportional representation would always place them in a minority position given that they only represented a small percentage of the population whereas the Sinhalese did not want its many sub-communities and castes to receive powers from the check and balance system from each government department[15]. Though the real issue among the political class had to do with representation, these government reforms leading up to independence in 1948 established the divide between the Sinhalese and Tamils, sparking separate identities and fostering an environment of division instead of unity.

Thus, the transfer of power from the British on February 4, 1948 was met with uncertainty for the political future of the nation. Attempts to introduce representation such that the minority groups like the Tamils would be able to effectively safeguard their interests were rejected by the British. Other political events such as how G.G. Ponnambalam would go on to support the United National Party, though criticizing the very same party earlier for not being progressive[16], also made the issue of supporting independence more complex than straightforward. What was certain was that there was an ethnic divide between the majority Sinhalese and the minority Tamils making up the majority of certain portions of this newly formed nation.

Flag of British Ceylon, prior to independence

Looking at this point in time, a mixture of colonialism and politics directly contributed to the growth and development of separate ethno-centric identities within a geographic space. There could be an infinite number of theories as to how these events may or could have played out differently so that modern day Sri Lanka could be more united and inclusive of all of its ethnic groups and communities. However, the path of developing separate identities and safeguarding interests at an ethnic level rather than a common, national level was one that was taken. To say that the war started with the events following Black July in 1983 is inaccurate to say the least; the issues leading up to those ethnic tensions coming to a peak go much farther back than independence day itself. Because of the history and interactions politically among the Sinhalese and the Tamils, the call for a united Sri Lanka in this modern day may also take a very long time to achieve, assuming that all groups are even willing to find a way to start building that bridge.

**Looking to create your love story? Join the other couples who have dated and got married through myTamilDate.com!***

"myTamilDate Love Story: Jenani & Nav Found Each Other At The Right Time And Right Place In Life"

"myTamilDate.com Love Story: Tharshi & Ravi Found Love During Lockdown"

"How France Met Canada: A MyTamilDate.com Love Story"

***CLICK HERE to listen to us on Spotify!***

WATCH NEXT:

[1] https://www.newindianexpress.com/states/tamil-nadu/2022/jan/13/special-cm-outreach-on-world-tamil-diaspora-day-2406203.html

[2] Raghuram, Parvati; Sahoo, Ajaya Kumar; Maharaj, Brij; Sangha, Dave (16 September 2008). Tracing an Indian Diaspora: Contexts, Memories, Representations. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9788132100393.

[4] https://www.thestar.com/opinion/commentary/2015/07/23/riots-helped-to-define-canadas-tamil-community.html

[5] Brass, Paul (18 June 2010). Routledge Handbook of South Asian Politics : India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. ISBN 9780415434294.

[6] Gunasingam, Murugar (1999). Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism: A study of its origins. MV Publications. pp. 108, 201. ISBN 978-0-646-38106-0.

[7] Vaitheespara, R. (2006). "Beyond 'Benign'and 'Fascist'Nationalisms: Interrogating the Historiography of Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 29 (3): 435–458. doi:10.1080/00856400601032003.

[8] Stokke, K.; Ryntveit, A.K. (2000). "The Struggle for Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka". A Journal of Urban and Regional Policy. 31 (2): 285–304. doi:10.1111/0017-4815.00129.

[9] Ibid.

[11] De Silva, K.M. (1972). "The Ceylon National Congress in Disarray, 1920–1921". Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies. 2 (1): 114.

[12] Wilson, A.J. (2000). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 1–12, 27–39, 66–81, 82–111, 124. ISBN 978-0-7748-0760-9.

[13] Russell, Jane (1982). Communal Politics Under the Donoughmore Constitution. Colombo: Tisara Publishers.

[14] Ibid.

[16] Wilson, A.J. (2000). Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism: Its Origins and Development in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. University of British Columbia Press. pp. 1–12, 27–39, 66–81, 82–111, 124. ISBN 978-0-7748-0760-9.