Genocide denial

Every year in May, the global Tamil community comes together to solemnly remember the profound tragedy of the genocide they endured. This period marks the Tamil genocide remembrance week. a somber occasion that prompts deep reflection on the heart wrenching final weeks of the Mullivaaikkal massacre. Despite our unwavering insistence on addressing, it as a genocide, the international response remains strikingly diverse. Many leaders, institutions and organizations either exhibit indifference or consciously avoid labelling it as a "genocide". Instead, they prefer terms like "massacre", "human rights violations" or "mass atrocity" to describe the unspeakable crimes committed. Notably absent from their discourse is the term "genocide". Although these expressions similar on the surface, they hold distinct meanings

The term "genocide' first emerged in print in 1944, appearing as both the title and subject matter of Chapter IX in "Axis Rule in Occupied Europe" by Raphael Lemkin - an International lawyer of polish-Jewish origin. Initially it referred to "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group", though Lemkin's conception of genocide is far more intricate. He coined the term by combining the Greek word "genos" (race, tribe) and the Latin suffix "cide" (killing), similar to words like infanticide, homicide and suicide. Lemkin even proposed the term "ethnocide" as an equivalent. He introduced this concept to encompass not only the actions against Jews by the Nazi regime but also its intentions towards ethnic groups with in the Reich, particularly in the conquered territories of Eastern Europe , where he is originally from.

What do genocides kill?

Lemkin's intention in coining "genocide" was to safeguard the right of national groups to exist, akin to how "homicide" protects the right to life of individuals. It's evident that what is extinguished in genocide is what precedes the Latin term "cide", defining the subjective nature of the crime. In the case of genocide, the focus isn't on the individual as the victim, but on a collective entity. Although the consequences of genocide destroys individual members, it's more accurate to characterize it as an assault on the group itself. This is because a group holds a significance beyond the mere sum of its individual constituents. Unlike a homicide that targets an individual, genocide eradicates something more immanent than an individual - the essence of the group itself. The essence that is eliminated is the unique identity, culture, and interconnectedness that define a collective entity. Therefore. the deliberate avoidance of denying the subjectivity of the crime, i.e., that the Tamil community is attacked as a collective raises a pivotal inquiry: How does it affect the memory of the fallen? The situation becomes clearer upon examining various instances of genocide across global history. Some genocides are widely recognized as prototypical models or core cases, notably the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and the Rwandan Genocide. In contrast, there are cases where the label "genocide" remains contested - often relating to indigenous populations and colonial-era atrocities. Additionally, some genocides have sadly slipped into oblivion over time, vanishing from the public consciousness. Regrettably, these events are frequently marginalized in academic discourse, memorials, and discussions. The tragic Hutu genocide in Burundi serves as a stark illustration. Alas, the Tamil genocide teeters on the brink of becoming another forgotten genocide, if the struggle for genocide recognition is not fought in political, intellectual and cultural domains.

The Armenian example

The Armenian community's tireless century-long struggle for recognition parallels the Tamil experience. While the Turkish government, the successor state to the Ottoman regime, still denies the Armenian genocide, Armenian diaspora have substantiated the historicity of their genocidal experience through meticulous academic research. Their immense contribution to the field of genocide studies predating government recognition and as a testament to their dedication to preserve the memory of their catastrophe. Just as genocide itself is a political process, the struggle for genocide recognition is equally political. If the decades-long national liberation movement fought for the right to exist as a collective, the struggle to recognize genocide is a battle for the commemoration of a collective loss or the loss of a collective.

In my pursuit to address this issue, I have delved into the reasons why the Tamil genocide shares commonalities with other acknowledged genocides and why it warrants acknowledgment and validation. This exploration forms the foundation of my master's thesis titled "Collective Genocidal Intent in Sri Lanka" which approaches the problem from the disciplinary standpoint of International criminal law.

Legal analysis

One prevalent rationale offered by international legal experts like the Navi Pillay for refraining from using the "G-Word" is the perceived absence of evidence linking the deliberate targeting solely because of their identity of Tamil ethnicity. In my thesis, I conducted a comprehensive analysis of this assertion. For any crime both the mental element i.e., mens rea and a voluntary act or omission i.e., actus reus are the fundamental elements in its legal form. Given that genocide is originally a legal concept, it encompasses a mental element known as genocidal intent or dolus specialis. While traditional understanding implies that the genocidaire's mindset is revealed through speeches and classified documents regarding the genocidal operation, this was possible in the case of the Nazis and the Hutu power movement which lost its status of power after the genocide bringing huge swathes of declassified documents and confident witness to the criminal trial. This is unlikely in the case of Sri Lanka at this point of time. However the absence of damning hate speeches by he top leadership or the confidential military documents detailing the bombing the no fire zones does not negate the occurrence of genocide. I contest in my thesis that seeking evidence from individuals does not determine the large scale criminality of genocide. It only determines the individual culpability. even that is dependent on the objective existence of overall genocide which can be determined through an analysis whether a substantial section of the Tamil community was destroyed and whether the destruction was systematic, non random, non- accidental, repetitive and the historical and political reasons for choosing Tamil community as an object of target. This determination hinges on objective factors rather than the subjective interpretation of the perpetrator's mindset

Way forward

In conclusion, for the commemoration of the Tamil genocide to become a global event of significance, it is imperative to recognize the profound loss incurred by the destruction of the Tamil community. This demands much more effort than what is currently being done now. The youth of the Tamil diaspora may consider pursuing careers in the genocide studies, in order to transform this concern into a tangible reality. I hope that my efforts will contribute to the ongoing attempts against genocide denial and apathy, ultimately fostering a more compassionate and informed global dialogue.

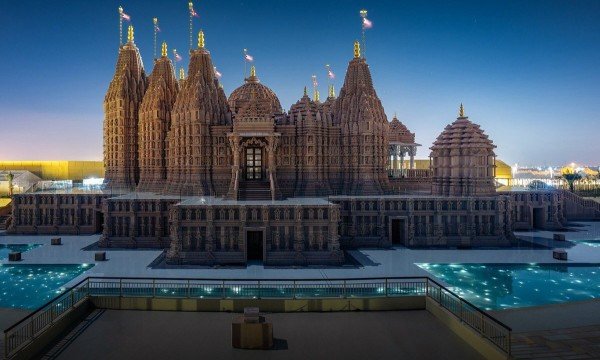

-Featured Picture credit - Kumanan

What is my Identity? It's a question that we all seek to answer in our own ways throughout our lives. Each episode of Identity spotlights a different creative, some from the Tamil community and some from outside it, who will be chatting about how we take ownership of our narratives, art, politics and of course who we are. Catch these episodes of 'Identity'!