myTamilDate.com has been the most trusted dating community for single Tamils around the world for close to a decade! It’s the premiere dating platform for diaspora Tamils and has the largest membership base in Canada, USA, UK & more. You can join the community for free at www.myTamilDate.com.

Do you prioritise your own happiness and goals, or do you put the needs of your family and community above your own? Or maybe you try to find a balance of both? For many older Tamils, there is often a priority placed on collective happiness, or at least the impression of it. This could mean putting someone else’s wishes before your own or putting the family before individual needs, even if it means unhappiness or distress for yourself. For many young people, on the other hand, individual well-being and wants can often take priority, and can clash with the more traditional approaches. What is the cause of these very different approaches to the way we live our lives? I would argue it comes down to the radically different environments diaspora Tamils grew up in, compared to those born and raised in places like Sri Lanka and India.

You might say, “well, that’s obvious.” But let me keep going. Growing up, looking at how my aunts, uncles and family friends approached their own happiness was fascinating, mostly because I couldn’t understand a lot of their values. They would often help people who didn’t treat them well, teach the importance of always putting your wishes second to those of your parents or those around you, and seemed overly concerned with how they were perceived by others. I didn’t get it. Especially as I got older, the things that seemed to matter more were my own happiness and my immediate family and friends. I didn’t care for random people or “what the community would think,” and my friends reinforced these ideas.

Why is it that in general, older and younger Tamils seem to have these radically different approaches to life? The answer, according to people who have researched this, has less to do with age and more to do with the influences around which we grow up. Studies looking at cultural differences in upbringing show very clear distinctions between “western” and “eastern” cultures. In the west, “high arousal” emotions like excitement, anger, happiness, and fear are more valued than in eastern cultures, where “low arousal” emotions like calm, relaxation, ease and pleasantness, among others, have greater social value.

- Tamil Innovators: Leadership Lessons With Trailblazing CEO Kasturi Chellaraja Wilson

- Tamil Innovators: Saeed Selvam on Finding Yourself in a Polarized World

- Tamil Innovators: Kumaran Nadesan on Realizing the Potential of the Global Tamil Community

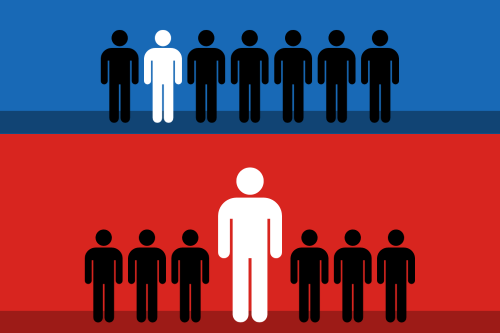

Western cultures predominantly revolve around independence. This puts the individual (you) first, and your thoughts and feelings before all else. Eastern cultures, like those in Sri Lanka, tend to value more interdependence, where your thoughts, feelings and actions are valued in their relationship to other people. I used to think this had more to do with age, or with some kind of “village mentality”; it must have come from living in smaller, more tight-knit communities, or resulted from the recent history of Sri Lankan Tamils. Since the 80s, the Tamil experience has been one of uprooting and resettling; doing whatever you can to look out for your family; and using newfound opportunities in diaspora countries to give those same opportunities to those around you. There was limited opportunity to truly “do what you want”. But as it turns out, this understanding is very narrow.

The way we operate is dictated by what gives us positive reinforcement. Research on this topic shows that people in western countries tend to have more self-focused emotions than eastern cultures. In a place like Canada, we’re used to getting praise for things like being a hard worker, professional success, and making money; if you have a good job and work long hours and hustle, you’ll likely earn some level of admiration and respect from those around you, which drives you to continue doing these things. If you’re a good caregiver, go out of your way to help others, and prioritise collective happiness over your own feelings, you may earn a few pats on the back and the admiration of your family, but it’s also possible that you’ll be seen by others as having less ambition, being a bit of a pushover, or as someone who doesn’t know how to say no.

This is the environment in which we grew up in as first-gen immigrants. But our parents and grandparents were overwhelmingly raised in environments that valued collective thinking. I’ve heard so many conversations from older relatives and family friends about their disappointment that their kids chose an unconventional career or to not get married, or their shock that a child refused to put their wishes second to those of their family. Looking at the behaviour of many of these older people, there is a clear value placed on fitting in, interdependence, and the collective good. Where the obvious tension arises is when the collective mindset of this older generation clashes with the independent views of newer generations.

If you were raised in an environment that taught you to put yourself first, you will likely continue doing so. If your environment taught you to put others first, you will likely continue to think this is the right way. If you grew up receiving one of these views from your family and the other viewpoint from society, you may have grown up confused by the conflicting ideas you felt. Have you ever judged the culture in the west that normalises putting your elderly parents in a care home? But at the same time, judged someone else for putting all their happiness and desires aside to support their family? These conflicting feelings are just another element of growing up under the influence of two very different cultures.

Understanding that the collectivist mindset doesn’t simply come from “not being with the times” helped me understand a lot more about my older relatives, and be more open-minded and empathetic to a value system I didn’t grow up in. Our differences aren't just generational quirks, but run a lot deeper. Understanding them can be a means to narrow the generational gap that often divides the old and young.

Graphic by Sobica Vinayagamoorthy

Kitayama S, Park J. Cultural neuroscience of the self: understanding the social grounding of the brain. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010 Jun;5(2-3):111-29. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq052. PMID: 20592042; PMCID: PMC2894676.

Lim N. Cultural differences in emotion: differences in emotional arousal level between the East and the West. Integr Med Res. 2016 Jun;5(2):105-109. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2016.03.004. Epub 2016 Mar 21. PMID: 28462104; PMCID: PMC5381435.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2010). Cultures and Selves: A Cycle of Mutual Constitution. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 420-430.

**Looking to create your love story? Join the other couples who have dated and married through myTamilDate.com!***