***Are you or someone you know in the global Tamil community doing great things? We'd love to feature them: FILL OUT THIS FORM ***

I told Kaila “Imagine what Thamizhs around the world would want to know about me and interview me for that community”. So here it is.

By Kaila Bohler

While Sugi was growing up she didn’t really think about whether or not she was Danish or Thamizh. In her teenage years she primarily identified as Danish - had Danish friends, went to Danish school, and didn’t attend a lot of Thamizh events. Even though she didn’t have this connection with the Thamizh community, her family made sure she kept her Thamizh roots. Her father impressed upon her the importance of learning Thamizh. “If you don’t keep up with it you’ll forget it at one point,” he would say. At home she would speak Thamizh and eat Thamizh food, but she would often be embarrassed to bring this food to school. She wouldn’t even wear Thamizh clothes unless it was a holiday. “Being a brown kid in a really small village in Denmark I just wanted to fit in. I didn’t even think about it back then. It was just the way things were. I wanted to belong.”

The diaspora Thamizh identity

As she got older, the distance she put in between herself and her Thamizh identity closed. In her teenage years she began to connect with Thamizh groups, primarily diaspora organizations involved with the support of the resistance back home. This involved fundraisers (i.e. the tsunami), lobbyism, and demonstrations.

She grew up independent compared to other Thamizh people, especially other Thamizh girls at that time.

It was difficult to be 100% of the Thamizh community because I knew I was different. Which I later learned that a lot of Thamizh womxn around the world felt like that. Like they didn’t fit in.

The Thamizh community is a very patriarchal society which eventually became too toxic for her, causing her to leave the organizations and Thamizh network altogether.

In her early 20’s she met and fell in love with a Dane. She began living on her own and going to university. This Danish lifestyle made her feel like she was losing her identity again. She wasn’t being exposed to the daily Thamizh routines like the ones in her parent’s house. After a few years she realized this and returned to her Thamizh heritage - by eating the food, wearing the traditional clothes, and celebrating Thamizh holidays. She started to decolonize.

Over the course of the next 4-5 years I found a more balanced way [of life] and figured out who I am: which is a diaspora Thamizh.

Identifying herself as diaspora Thamizh came both with privilege and a sense of guilt. And the guilt was overwhelming. The more she continued on her journey of healing and decolonizing the more she learned about herself. She struggled to break free of the guilt imposed by the societal structures, but eventually found a way.

I learned how to not be guilty by my privilege. The privilege of education, socioeconomical status, the privilege of not being in the war in the first place. It wasn’t my choice to leave the homeland. But at the same time finding a way to use that privilege to do something good in whatever capacity I had.

READ NEXT: How France Met Canada: A myTamilDate.com Love Story

Back to the Homeland

Sugi first visited the Thamizh homeland when she was 11-years-old. “I’m home,” she thought, “I look like everybody, I fit in here.” After more trips she realized later that she didn’t exactly fit in. She could speak and dress like a Thamizh, but she couldn’t escape “looking different.” Whether it be the way she presents her hair or in the way she walked, she always felt like somehow she didn’t belong. She didn’t belong there or in Denmark.

A lot of diaspora kids go through that trouble, [wanting to belong].

She eventually found that she could use this double cultural identity to her advantage. Using her privilege to support and work with people in the Homeland.

It was about embracing that I was a diaspora. People in both places are my community

She continues:

The friends I have here [in Denmark and countries close to Denmark] that I share my heart with are as much my family as my friends back home [Thamizh homeland] who I share my heart with. It’s about finding the balance between that.

The mental breakdown

Sugi was going through a rough time in her late twenties - she was working full-time, studying full-time, and the man she had been dating for over 8 years was struggling with severe PTSD for most of those years.

She told her friends over and over again, “I need to breathe.”

Her family and friends didn’t completely understand that sentence and how deeply she was consumed by her depression and anxiety. In the winter of 2017 she had a mental breakdown and couldn’t get out of bed. She was put on sick leave for almost 3 months.

I think I scared everyone around me including myself. My parents are used to seeing me as this strong womxn and hard worker and one day I just broke down. Mental illness and the impact of having a family member or partner with mental illness is not something we are used to talking about in Thamizh society.

In those months Sugi talked a lot about mental wellbeing with her mother and how she wanted to live her life. It was completely by accident that she found herself on a boat.

I don’t think I had ever been on a boat before,” Sugi recalls. “It just made sense.

It started with looking for a cottage in the countryside where I could go and stay whenever I needed a break. Suddenly I was looking at a boat online.

I went to go look at a boat and the next thing I knew, I bought it.

She felt connected with her ancestral history since the womxn of her past would go out fishing and be independent. Even in recent history womxn’s liberation was an integral part of the fight against oppression, erasure and genocide. She appreciated the freedom that a boat granted her, an escape from her hectic life working as an interdisciplinary journalist writing, photographing and documentary filmmaking. She named her boat Kadalmagal, which means “The Daughter of the Ocean''.

Having my ancestors guiding me in my heart, I took on the venture of learning to sail by myself. I started by just sailing out of my parking spot, turned around and sailed back in. And for every time I would sail a bit further. But jheeez, I was scared like hell”, she laughs.

Her partner and she broke up but still remained good friends.

The boat was a blessing for her mental health, especially during the pandemic. The freedom gave her the time to work on her start-up and tune back into her creative mind.

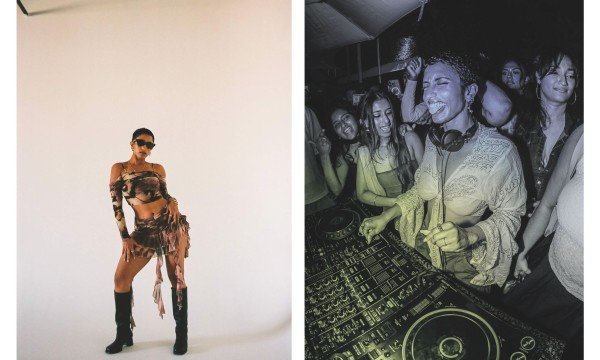

Creating AnbudanSugi

She saw her friends calling their kids in the language of their second language; ‘darling and honey’. The more being born into the diaspora, the fewer people will be using the language, she says.

I wanted to inspire people in their own capacity to explore the part of their identity that is Thamizh.

She wanted to create products in the Thamizh language to foster and encourage people to use Thamizh words when they talk with their kids in order to help them be excited about the language.

One of her t-shirt designs says “adakka odukkamaana pillai” , which translates to “decent girl” in a cultural context. Every Thamizh womxn has heard this at least once in their lifetime. Either that they’re not decent enough or that another girl was more decent than them. This comment could be simply having loose hair or a “too short” skirt; anything that could be considered immodest/not decent by the viewer. The word is accompanied by a copyright symbol signifying that the idea of decency is up to the individual to define.

I want the next Thamizh generation to define themselves. If you are true to yourself, you can’t be anything but decent. You shouldn’t let others define what is right for you, what is decent. We need to start these conversations with those [Thamizs] around you. With your mom. With your aunts. Anyone. I think I missed that as a young diaspora woman.

Starting the conversation

In the process of designing that t-shirt, she had conversations with her mother. The second her mother saw the design, she sparked the conversation Sugi intended with that design. Actually to just start the conversation.

We didn’t define what a decent womxn was in Thamizh culture, it was so unspoken and the minute you cross that invisible line, you’ll be blamed and stamped.

In her early years she had felt like she was unable to talk to her mother about it, because it was unspoken. Her mother brought her cultural identity here not fully recognizing that her daughter was growing up in a completely different environment. Sugi also had to come to terms with the fact that her mother came to a strange, new country, far away from everything she had known.

Another design is ‘Naadoodi’ which roughly translates to “Wanderer.” The script is paired with images of the palmyra leaf which are an important symbol within the Eezha-Thamizh community.

That perfectly describes being a diaspora, not just diaspora Thamizh, but anyone. A diaspora that has [constantly] searched for belonging in different countries. And for Thamizhs the palmyra leaf symbolizes our roots and heritage.

She continues:

I didn’t live in four countries before I was 30, but I definitely searched for belonging to every place that I went. Today I have people in Karaikal (Tamil Nadu) that I call family, and one of my best friends lives in London, another lives in Norway, and another in the Homeland. I think that’s beautiful. It’s a privilege to call someone family, to be able to choose your family.

Eventhough Sugi didn't move around from country to country, she sees herself as a 'naadoodi' because of what it means and symbolizes:

That word just describes the beauty of it. I’m diaspora Thamizh. I’m a wanderer, and that's beautiful. And I hope to inspire other people to see that as well...And my story is not very different to other diaspora womxn.

The integration of Thamizh heritage and Scandinavian design

At AnbudanSugi she tries to implement the values of the Thamizh heritage and resistance movement. One thing you notice on the website is there are no “gender markers”. The clothes are combined in one “Identity Collection”, explaining the shapes of the clothes as “straight cut” or “curvy cut”.

The Thamizh liberation movement was inclusive in all forms, especially when it comes to gender and that is important for me to continue.

A major thing she was missing in her life growing up was having her Thamizh identity being visible. The Thamizh language and culture mixed with Scandinavian or western designs of her products will hopefully inspire more Thamizhs to learn about and express their own Thamizh identity.

Follow AnbudanSugi on Instagram!

READ NEXT: How France Met Canada: A myTamilDate.com Love Story

***Looking to create your love story? Join the other couples who have dated and got married through myTamilDate.com!***

"How France Met Canada: A MyTamilDate.com Love Story"

"How a Message on myTamilDate.com Led to an Engagement for Lavanya & Vitharan"

Related Articles:

- "How A Daily Ritual and Family Heritage Inspired a Multi-Million Dollar Company: Meet Sashee Chandran, Founder of Tea Drops"

- "Danny Sriskandarajah's Journey From Rural Sri Lanka to CEO of Oxfam Great Britain"

- "Meet Tamil-Canadian Tech Entrepreneur Mano Kulasingam"

- "The NBA Bubble: Dr. Priya Sampathkumar Helped Make It Happen"

- "These Tamil Founders Behind Agritech Startup Dunya Habitats Want To Alleviate Food Security Globally"

- "Marketing Maven Jackson Jeyanayagam Shares Insights From His Illustrious 20-Year Career"

- "Angel Investor Jay Vasantharajah On Building His Portfolio One Day At A Time"

- "Meet Tamil-Canadian Journalist Kumutha Ramanathan"

- "Breaking Into Hollywood: Meet Tamil-Canadian Actor Vas Saranga"

- "Meet Rebecca Dharmapalan - Filmmaker, Legal Scholar, And Activist"