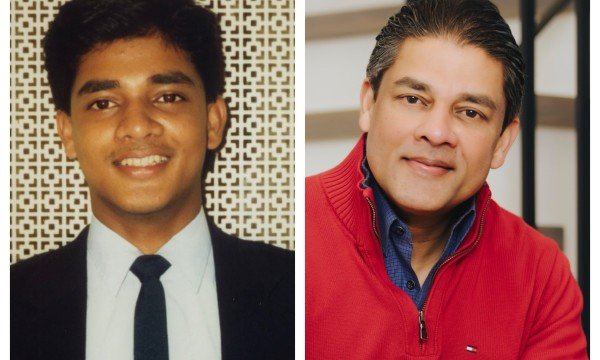

Thirty-seven years ago, on April 18, 1988, I was in a taxi with my parents that was heading to the Colombo airport in Sri Lanka. It was eerily quiet inside. Appā (dad), Am’mā (mom), and I sat muted as the taxi fought through chock-full of loud traffic: cars, motorcycles, rickshaws caught together in the heat. Despite this, it was an uneasy silence; I remember breathing the hot musty air blowing into the taxi through the wide-open window. I was leaving for Canada. My parents didn’t know what the future held for me.

Even though the events that led me to this were out of their control, at some level, I thought they felt that they had come up short in providing for their son. It was very clear to me that I was more important to them than anything else in this world. But here they were put in this position. The silence inside the taxi was broken only by the honking of all varieties of horns and the nervous beating of human hearts. The loudest sound I have ever heard in my life.

Once I finished my check-in routine at the KLM counter, it was time to say my goodbyes to them. I gave Am’mā a tight hug, and she landed a thousand emotional and warm kisses. Then it was my Appā’s turn. We hugged it out a few times. The final parting words from him, as he gave his last hug: “In Canada, you will have opportunities that I never had.”

“Yes, Appā,” I replied quietly.

“Don’t squander them away. Study hard. “Work hard.” He didn’t stop. “Do what the locals do to assimilate.” Then, as he presented me with a beautiful blue striped tie, a heartfelt request made in a trembling voice: “Throughout last year, I’ve asked you to do many things. Therefore, it should surprise you little that I have another thing to ask of you. I ask that you live.”

I landed in Toronto on April 19, 1988. At the age of nineteen. Alone!

Two days after I landed, on April 21, 1988, Appā was killed by a single bullet. He was only fifty-three. A single bullet made his soul depart to the celestial planes, to walk with his ancestors. A piece of me gone; my flesh and blood, my father, myself.

I was broken-hearted, lost and at a crossroads in my life at that young age. That’s when I got my first office job at a small investment firm on Bay Street. The people I met there treated me with great kindness. It bowled me over.

Acknowledge. Assimilate. Move forward. That's how you win.

Despite this, I brought a lot of self-loathing to the table when I was young. I was an angry kid. Had I not become a mailroom boy at the age of nineteen, I would have spiraled into a world of despair, darkness and destruction. I wouldn’t have made it out of my twenties or the bad predicament I was in at the time, for sure.

It was the first time I had a reason to respect myself. It was the first time in Canada I had direction in my life. It was the first time I found myself in the presence of people I respected and whose ‘favorable’ opinion of me I yearned for. Many decades later, I’m still not a reliable narrator of my own life. I still screw up a lot.

But it has been an amazing ride, and I have learned many lessons along the way: If you subsidize undesirable behaviour, you will get more undesirable behaviour. Hard work wins. The world doesn't owe you comfort. It owes you opportunity. Seize it. You can’t control the outcome—but you are one hundred percent in control of the effort. And before blaming other people, get to the nearest mirror and ask yourself— “what could I have done to change the outcome?” Don’t tacitly relinquish responsibility for your welfare to someone else. If you do that, you may be the last to know of the potential changes that will impact your life.

Initiate action or spend all your time reacting. Most react. They follow. They absorb whatever they are fed without question. If you want to be happy—if you want to be successful in life—don’t sign up to groupthink. Break free from the herd. Think. Question. Decide for yourself. No one cares about how you feel. The world rewards action, not emotion. You can cry, complain, or scream at the world—or you can get to work. Only one of those changes anything. Focus on your family, fitness and finance—and your faith, if you have one.

Everything you want is behind a wall of hard work. The body you want, the achievement, the respect—it all comes at a cost. The question is, are you willing to pay it? Most people are slaves. Not to chains, but to habits. To distraction. To the opinions of others. Real freedom comes from control—of self, of mind, of desire. Ruthless self-discipline is the solution to free us from the invisible chain imposed by habits. In the interest of full disclosure, I’m still struggling with this.

All your right actions are evidence of your great potential, and all your screwups are the mistakes of inexperience, which will be corrected, surely, by the passage of time. Mine have. To write a poor sentence in your book of life at the age of nineteen is expected, and I have written many bad ones. They were all quickly forgiven. But to write an entire book with poor sentences about your life is inexcusable.

Though past events are unchangeable, they can serve as important lessons in overcoming the struggles of life to strive for a better future. We are all worthy of a life we desire. But it can only happen under the right conditions. Canada provided me with those conditions: freedom and choice. It was prosthetic to my amputated spirit.

But things are different now.

I don’t take what I have for granted. It’s a fleeting thing, and it could evaporate at any minute. “Be grounded,” I find myself saying this often. Sometimes I’m unsuccessful in this quest. It’s a small price to pay for not skipping meals like I had in my early days in Canada. An empty stomach and broken soul taught me many valuable lessons. It afforded me a lot of luxury and freedom, and I’m no longer behind on rent. I’m not hiding from the credit card company.

I never realized what a naked parallel that Appā’s tragic story was to my current blessed life. Not for his ambition that was snuffed out by his untimely death, not necessarily for the things he couldn’t do, but for how, at the same exact age as he lost his life by dying, I gained mine by living many decades later. It wasn’t a specific accomplishment he had invested all his pride and hope in, but a specific condition in which that accomplishment had been achieved by someone other than him. His legacy. Me. A sign of living. A daily salve for my red, angry, and unhealable wounds.

My Appā knew, in Canada, I would have opportunities that he never had. He didn’t send me here to just survive—he sent me here to live.

The tie he gave me at the Colombo airport still stands as a symbol of this hard-won battle.