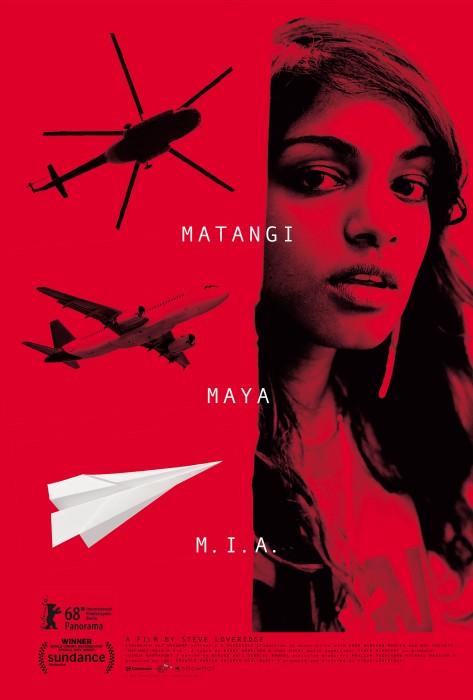

The London autumn evening is winding down. After dinner, my sweetheart and I sit together on the sofa in front of the TV, and patch in the laptop video feed. I click on the link to an advance viewing of the forthcoming documentary, Matangi/Maya/M.I.A.

The UK-based Eelam Tamil music star is familiar to us both: we are children of the Tamil diaspora. My partner was born in Sri Lanka, growing up in rural Germany after her parents fled the conflict. I was born in small-town Canada; my earliest memories are of family members arriving from Sri Lanka, using words like “refugee” and “bomb blast.” To us, MIA was the first cultural representation of Tamils we’d ever had on the international (well, Western) stage.

As the documentary opens, it’s clear to us that the camera’s lens carries a warm relationship with its subject. The footage is completely derived from home video recordings, filmed by her close friends and by Maya herself. At one time, she’d wanted to be a documentary filmmaker. The intimacy of the film is arresting; and Maya’s vulnerability throughout much of it will probably shock anyone who’s seen her external persona.

On screen, a teenaged Matangi reads Fanon and drinks wine from the bottle, telling her friends, brother, and sister that their dad’s absence made her more resilient.

As most people know by now, Arular (who M.I.A.’s first album was named after) was a notable of the Tamil struggle; a founder of the Tamil Resistance Movement which was banned in Europe at the same time as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. He attributes his absence to smuggling ammunition and explosives into Sri Lanka, hidden under the clothing and trinkets he’d bought for his children.

As Matangi says the words, she’s equal parts convinced of herself, and on the verge of tears. The resilience that Arular’s absence instilled may have made her into the international superstar she is, but her journey is also one of recovery from the grief it caused at such a young age. My sweetheart and I exchange a glance. We both know more about that feeling than either of us cares to put into words tonight.

It’s not just grief that propels the young woman, though. It’s alienation. Like us, Maya was possibly the only student of colour in her school. She describes her first exposure to hip-hop music in a Council flat—low-income, government-subsidized housing in London. Her neighbours had robbed her. The only thing she asked them to return was her stereo, which she used to listen to pop music as she fell asleep. They wouldn’t give it back, and that night she had to listen to the noises from the other apartments. The insistent bassline from a neighbour’s sound system: Public Enemy. A point of entry, if you will.

Camera in hand, Maya heads to Sri Lanka in 2001 to document the conflict. The ceasefire hasn’t quite come into effect yet; Maya wonders if she should peel the visa off her passport and get a new one because it categorizes her as a journalist – and “they do shoot journalists.” “I was there in January 2001” my partner interjects. So they were both back home just a couple of months apart.

Maya confides being sexually assaulted by Sri Lankan military men on the Colombo bus, during that trip – “yeah, you don’t ride the bus in Colombo,” my sweetheart tells the screen. Maya responds into the camera how she thought, in that moment, about the fighters in the jungle. How they were the only ones who stood between the Tamil people and complete indignity.

As she tells us this, I remember the way I felt in early 2009. It was becoming clear that the Tamils were losing: daily being murdered across the homeland. That feeling of overwhelming powerlessness. It changed the entire course of my life. Biracial or not, Tamil-speaking or not, I could never choose to stand on the sidelines of this movement again. The fighters are gone now. Securing our dignity is our own job.

Of course, 2009 changes MIA’s life too. Her platform now established, she takes to social media and the talk-show circuit to expose the genocide. But Bill Maher prefers to ask her why she talks like a Cockney when she’s from “Shrea Laynka,” and nobody pays attention to the footage of war crimes that she’s tweeted out.

When she dramatizes the extrajudicial execution in “Born Free”—by casting gingers as the victims of genocide—it forces these folks to see that there’s nothing special about them. It could happen to them too. They hate her all the more for reminding them; they complain about the video. She gives them all the middle finger at the Super Bowl. “But she’s not even an American,” whines the blonde news anchor.

Towards the end of the documentary, MIA is now speaking at a public event on sexual violence against Tamil women. “I was supposed to be there,” says my partner. “We were all supposed to go as a group of Tamil activists, but the men took our spots and told us, ‘maybe next time.’”

So the three Tamil women activists didn’t get to see MIA after all, and they went out for dinner, as the event on sexual violence against Tamil women continued without them. Because within the struggle, there’s the struggle. And as a racialized public figure, as a Tamil political activist, and as a woman, MIA lives that layered struggle.

At this point, my sweetheart and I understand. Anyone who doesn’t love MIA doesn’t understand Matangi’s longing for her father to just be a father, not an absent hero. Those who attempt to degrade MIA don’t see Maya on the bus with the soldiers, wondering what her life would be like if she she’d become a guerilla, able to fight back. Those who mock MIA’s intellect and her achievements don’t see the strategist using her platform for a cause.

These attitudes towards the West’s first Tamil superstar are only possible for one reason. The cameras that have given us our images of MIA have never been held by people who wanted us to understand her for who she was.

Until now, that is.

And now, we understand. Matangi, Maya, M.I.A. In every phase of her journey, she’s us.

Movie Information:

Official website - https://www.miadocumentary.com/

UK theatres - https://www.miadocumentary.co.uk/

LA (@ ArcLight Cinema) - https://www.arclightcinemas.com/movie/matangi-maya-m-i-a?movieId=HO00012621&LocID=1001&TabID=0&IsFrom=CS

NY (@ IFC Center NY) - http://www.ifccenter.com/films/matangi-maya-m-i-a/

Montreal (@ Cinemx Du Parc, English - Original Version starting on Oct. 12th) - https://cinemaduparc.com/en/film/matangi-maya-m-i-a_fr

Toronto (@ Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema on Oct. 5th) - http://bit.ly/2PSvfvl

If you don’t see your city or town, please request a screening here: https://www.miadocumentary.com/screening-request/