“What’s with the stache, bro?”

“It’s a token of my prostate cancer awareness campaign for Movember,” replied Mayooran, sporting a smirk while wolfing down what was left of his tuna salad sandwich. “I’m not really fundraising for the cause – it’s just to avoid shaving for a month and to rebel against the norms of manscaping,” Mayooran added, chuckling.

“Are you serious?” asked his friend Mithunan. “If you’re going to hold out on shaving for a month, you’d better know that misshapen peach fuzz doesn’t count!”

“Oh, I’ll have one of those playoff beards – you’ll see!” beamed Mayooran.

Mayooran was an intelligent and carefree youth who nonetheless stayed faithful to his responsibilities at home and at school, but remained an alien to personal hardship.

“Wanna catch the rest of the Ottawa – Toronto playoff series at Mulligan’s?” asked Mithunan, excitedly.

“Nah, I have to bring my dad to a doctor’s appointment tomorrow morning – I can’t be hammered when translating English to Tamil, ya know!” replied Mayooran, smiling broadly.

“I gotcha man, no worries,” said Mithunan.

At home, Mayo poured himself a glass of orange juice and prepared to head out for a jog.

“Aren’t you planning to eat a proper dinner, Mayooran?” asked his father, Rajalingam, waiting patiently for a response. Rajalingam’s gruff voice had a way of nudging a response out of Mayooran.

“No, uh . . . I actually just had a tuna sandwich,” said Mayo, haltingly.

“He is on one of those absurd diets,” quipped Mayo’s mother.

The following morning, Mayo and his father met with their family doctor. “Your father had blood work done for a measurement of PSA, and I’d like to refer him to an urologist,” said the physician.

“What’s a PSA used for?” asked Mayo.

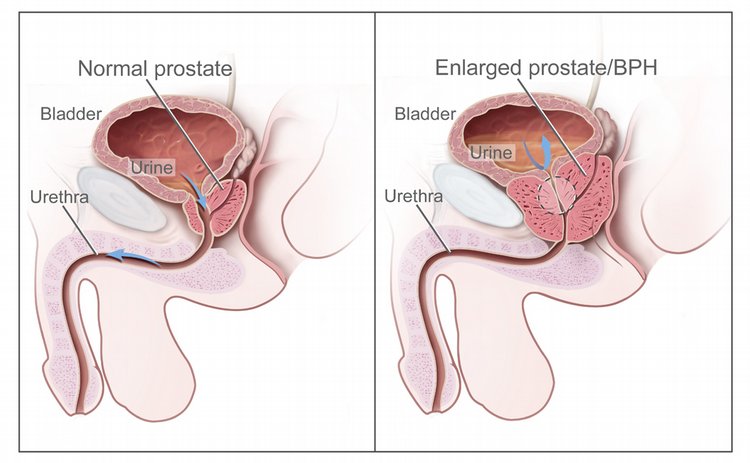

“An elevated (rising trend) PSA is an indicator of possible prostate cancer.” Mayo had realized he had been living in complete ignorance of this disease.

A few months later, Mayo and his father were at a hospital completing another measurement of Rajalingam’s PSA levels, followed by a review of the results at the urologist’s office.

“I’m concerned about your father’s PSA results,” said the urologist. There was a sense of urgency in his voice while his eyes were affixed to a sheet of paper. There was no attempt at conversation – just a raw delivery of the facts. At this point, Mayooran felt that his father’s life was in danger. I’m concerned about your father’s PSA results! The sentence rang out cacophonously in Mayo’s brain, like a child playing with cymbals.

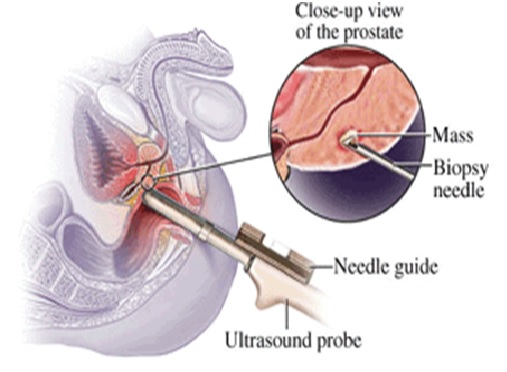

“I’d like to do a prostate biopsy,” said the physician, tersely.

“So the PSA test for prostate cancer . . .” Mayo said, nervously, before he was interrupted by the physician.

“The PSA measurement is not a test for prostate cancer. A prostate biopsy is a test for prostate cancer. Your father’s PSA levels are high, and I’d like to do a prostate biopsy. The PSA measurements are a screening tool. A prostate biopsy allows us to examine samples under a microscope for cell abnormalities that are a sign of prostate cancer.”

“What are the risks?” asked Mayooran.

“There is a risk of infection with the biopsy, but your father will be given antibiotics. The ultrasound department will take 8 samples from the prostate.”

After translating the discussion to his father, Mayooran seemed to gaze into a bottomless well of uncertainty. But he later had a serenity that came with the choice of the treatment he wanted for his father. “My father will complete the prostate biopsy for the benefit of knowing if there is cancer in his prostate.”

“We have another one!” yelled the doctor to his secretary, instructing her to book the biopsy. They were scheduled for the following month.

Donning a blue gown, Rajalingam entered the procedure room for his prostate biopsy.

“Would you like to remain in the room as I perform the biopsy?” asked the radiologist.

“Yes, I’d like to translate what is happening,” said Mayooran, gulping.

“This will take all of 15 minutes; we will be taking 8 samples. Tell him that each time we extract a sample, he will hear a click, like that of a stapler. Your dad will get a local anaesthetic,” said the doctor. Mayo promptly translated.

The doctor began and Rajalingam bellowed in agony. Mayo felt devastated. He assured his father that they were going to get through this together.

“Let him know that I will now apply anaesthetic before taking samples. I will count to 3 before extracting each sample,” added the doctor. Mayo nervously told his father of the up-count. Each up-count to 3 seconds was a living nightmare in which Rajalingam shouted and sobbed in pain.

“Did you bring me here to have me killed?!” cried Rajalingam.

“Did you give him the anaesthetic?!” Mayo asked, feeling absolutely helpless in the situation.

“It’s in there,” replied the doctor.

The biopsy was done. Rajalingam remained crouched in the fetal position until slowly rising to his feet to leave the room. He dressed and later sat in the waiting room.

“Dad, how are you feeling?” asked Mayo, cautiously. Rajalingam firmly held his cup of water and offered only silence.

A week later, they followed up on the prostate biopsy results with the urologist.

“His results are not serious as to warrant radical treatments such as surgery,” said the doctor, confidently. “We will continue to monitor him through regular PSA measurements. Active surveillance is a conservative management option that closely monitors men with low risk prostate cancer with regularity to ensure that aggressive cancers are detected and amenable to cure, yet avoids over-treating men with insignificant disease (Alves, 2011). Continue to live as you normally would,” he offered with a smile. “One in seven men – that’s me and you – will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime.”

“I felt like I was being tortured in that biopsy for these results,” said Rajalingam, after having discussed them with Mayo.

“Would you rather live in ignorance of prostate cancer?” asked Mayo.

“Appa: we live in a time and place where we should be grateful for having access to these medical advancements,” observed Mayooran, with his arms draped reassuringly across Rajalingam’s shoulders.

“Besides, it can’t be as bad as it was for Amma when she gave birth to me, right?” They laughed.

References:

Alves, P. (Fall 2011). Active Surveillance: Why an increasing number of prostate cancer patients are opting to wait rather than obtain treatment.

Retrieved June 16th 2013 from www.issuu.com/imsmagazine/docs/imsfall2011

Mayo Clinic. Prostate Biopsy.

Retrieved June 18th from www.mayoclinic.com/health/prostate-biopsy/MY00182

Prostate Cancer Canada www.prostatecancer.ca