Though lost, we know that Keechaka Vadham derives from the Virata chapter of the epic Mahabharata—the ancient text in translation by John D. Smith, not the nadagam on Vijay TV. Some of Mudaliar’s family felt that the material was inappropriate but he thought it had the perfect elements to make a film. How much of this story is similar to what was filmed can’t be known, but what is known is that the drama between Kicaka and Draupadhi and his death as the main plot of the film.

A few chapters before Virata, Yudhisthira, thick moustache and eldest son, loses a game of dice that is rigged by a combination of Sakuni, Duryodhana, and Dhritarashtra twice for which the resulting punishment is for all five Pandavas, brothers, and Draupadhi, wife of all five, must “enter the forest for twelve years, clad in the skins of ruru deer, then dwell for a thirteenth year unrecognized in a populous place, and if recognized, for a further twelve years in the forest…And when the thirteenth year is completed, the kingdom is to be returned again, by us or by yourselves, to its rightful owners.” War, exile, minorities, and dual identities—even ancient texts have an eerie and odd way to predict the future and the themes with which we would be negotiating our lives.

Fast-forward thirteen years later to the five brothers and Draupadhi taking on various disguises. They go around asking, “How will you pass your days in the King’s presence? And what will you do as you about in disguise?” They each come up with new identities and names that will help them disappear into the fabric of another society, but each new self contains essential parts of who they were before—it is impossible to shake their former selves, no matter how hard they try.

Each of their roles happen to be practical work, manual labour that can be accomplished with the body and where the only requirement is time and a servitude to a higher power—modern day slavery. It’s a position and possibility that immigrants find themelves in and how from a saree blouse, a medium double-double, an oil change, and a cut from a cardboard box that they are able to survive, thrive, and succeed away from home. By and with themselves.

When I read this section of the Mahabharata, I see it not as the way that Gods disguise themselves as warriors and devas by force and fear of being recognized and the ensuing trouble, but the way that immigrants and minorities try to pass in societies that would rather not have them exist, or act like they don’t for fear of revealing the loose seams of society, and how they function under the King’s white gaze.

The position the characters of Dheepan find themselves in when they reach Paris. The kingdom that holds them. Renaming yourself can have a power of its own and reclamations of self, but it often feels like an act of colonization, erasure. The brothers reply:

YUDHISTHIRA: I shall become a courtier of that noble king in the guise of a Brahmin named Kanka, a keen gambler who knows the way of dice.

BHIMA: I think I shall approach King Virata claiming to be a master cook named Ballava. I shall cook him soups, for I am skillful in kitchen work…and if there are wrestlers who will wrestle with me in the ring, I shall lay them low to make him happier still.

ARJUNA: I shall claim to be a eunuch…I will deck my ears with earrings that flash like fire, and braid the hair of my head…in woman’s form I shall amuse the king and those who live in the women’s quarters by reciting tale after tale.

NAKULA: I shall become King Virata’s master of horses.

SAHADEVA: I shall become King Virata’s overseer of cattle.

And then Draupadhi, who Yudhisthira says, “does not know how to do the work that other women do. She is a delicate maiden, a princess of high repute, a noble woman intent on serving her husbands: how will she go about? Since the day of her birth, this lovely girl has known nothing but garlands and perfumes, ornaments and clothes of every kind,” responds to the husband who in the first game of dice he lost put her up as collateral: “Maidservants work for others…but live in the world independently; convention does not permit other women the same freedom to come and go. So I shall claim to be a maidservant, skilled at hairdressing; if you seek after me, this will be how I shall disguise myself. I shall serve Sudesna, the king’s wife of high repute. Once I am with her, she will look after me, so do not be so troubled.” She re-names herself Malini and, in a reversal that betrays her caste, the served begins serving.

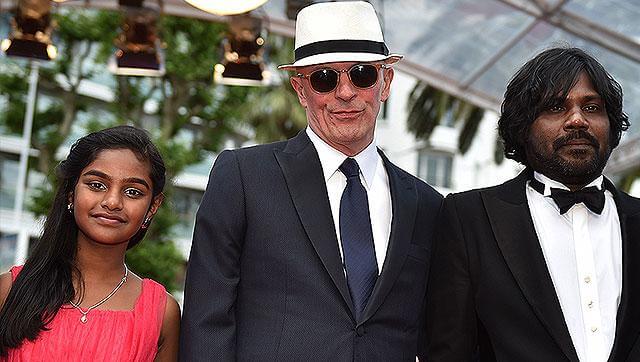

In his interview with The Guardian, Audiard continues: “I just wanted elephants in my film… and an image of nature moving. I don’t know what Tamils dream of. But what interested me was this—we see migrants as people who have no faces and no names, no identity, no unconscious, no dreams. And what happens to all the violence they’ve been through? I wanted to give them a name, a face, a shape—and give them a violence of their own. It’s a naïve film, really.”

To not understand the significance of elephant imagery to a Tamil, or a Hindu, and to include it in a film about Tamils—to assert the idea that Tamils are so different from French or white people, that they have specific types, that they don’t dream the same way that people do, to express racist and ignorant sentiments towards migrants and their lived experiences and history, and to use colonizing and appropriative language to describe how what you attempted to do with your power is naïve and f***ed up.

Jacques Audiard doesn’t see Tamils as people; he explicitly expresses his idea of them as Other, alien—like creatures, yet he decides to make a film to put them on the map-except that we’re already on it. We have difficult long names, beautiful, fair, dark and lovely faces, and a violence of our own—one that didn’t need to be given to us by him. Maybe his research happened to gloss over the almost 100 years of Tamil cinema, Kollywood, that began in 1917 when his ancestors were colonizing around the world. 100 years later, they still are.

To Be Continued...